1

INCOMPETENT TO STAND TRIAL

SOLUTIONS WORKGROUP

Report of Recommended Solutions

A report of recommended solutions presented to the California Health

and Human Services Agency and the California Department of

Finance in Accordance with Section 4147 of the Welfare and

Institutions Code

N

ovember 2021

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Purpose of the Workgroup and Report ………………………..

3

II. Incompetent to Stand Trial Crisis – a History ………………

5

a. The IST Process ……………………………………………..

5

b. National Data and California Data …………………………

6

c. Individual Patient Characteristics .………………………...

9

III. Department of State Hospitals Efforts to Date ………………

11

a. Increased Capacity at DSH ………………………………

11

b. Systems Improvement ……………………………………..

15

c. Demand ………………………………………………………

17

IV. IST Solutions Workgroup Process …………………………….

19

a. Guiding Principles for Generating Recommendations .…

20

b. Process for Synthesizing Recommendations ……………

21

V. Census of Recommended Solutions from the IST

Workgroup Meetings for Submission to CalHHS and DOF ...

22

a. Short Term Strategies: Solutions that can begin

implementation by April 1, 2022 ……………………………

22

b. Medium-Term Strategies: Solutions that can begin

implementation by January 10, 2023 ……………………...

31

c. Long-Term Strategies: Solutions that can begin

implementation by January 10, 2024 and

January 10, 2025 …………………………………………….

50

VI. Appendix A: IST Solutions Working Group Membership and

Affiliations ……………………………………………………….

65

3

I. Purpose of Workgroup and Report

The Legislature enacted Welfare & Institutions Code (WIC) section 4147 through the

passage of Assembly Bill 133 (Chapter 143, Statutes of 2021) and the Budget Act of

2021 (Chapter 69, Statutes of 2021), which charged the California Health & Human

Services Agency (CalHHS) and the Department of State Hospitals (DSH) to convene an

Incompetent to Stand Trial Solutions (IST) Workgroup (Workgroup) to identify

actionable solutions that address the increasing number of individuals with serious

mental illness who become justice-involved and deemed Incompetent to Stand Trial

(IST) on felony charges.

The purpose of the Workgroup is to identify solutions to advance alternatives to

placement in DSH restoration of competency programs and includes strategies for

reducing the number of individuals found incompetent to stand trial; reducing lengths of

stay for felony IST patients; providing early access to treatment prior to transfer to a

DSH program; and increasing diversion opportunities and treatment options, among

other solutions. Per WIC Section 4147, the Workgroup must submit recommendations

to CalHHS and the Department of Finance on or before November 30, 2021, for short-

term, medium-term, and long-term solutions that provide timely access to treatment for

individuals found IST on felony charges. The IST Workgroup convened between August

2021 and November 2021 and held five meetings and nine topic-focused sub-working

group meetings with a number of representatives and stakeholders from several state

agencies, the Judicial Council, local government and criminal justice system

representatives, and representatives of IST patients and their family members.

This report describes: 1) the background of the increasing numbers of referrals of

individuals committed as IST in California and across the nation, 2) an overview of the

IST Workgroup and the process utilized to develop the recommended solutions, and 3)

a census of recommendations provided by the members of IST Workgroup and

stakeholders to the CalHHS and Department of Finance.

The census of recommendations provided in Section V represents the gathering of the

collective discussion and recommendations from members of the IST Solutions

Workgroup and sub-working groups and input from public participation in the meetings

of these groups. Consistent with the direction provided by statute, any

recommendations that did not represent actionable short, medium, or long-term

solutions are not included. These recommendations do not represent the viewpoints or

opinions of any one entity or the State, nor do they represent consensus of the

members of IST Solutions Workgroup. Some IST Solutions Workgroup members may

support or oppose specific recommendations. All recommendations received by the

Workgroup, meeting minutes and specific support, opposition, and feedback by

individual IST Solutions Workgroup members and the public may be found at the IST

Solutions Workgroup website:

4

• https://www.chhs.ca.gov/home/committees/ist-solutions-workgroup/

IST Solutions Workgroup Members and their affiliations:

• Chair: Stephanie Clendenin, Director, California Department of State

Hospitals (DSH)

• Stephanie Welch, Deputy Secretary of Behavioral Health, California Health and

Human Services Agency

• Nancy Bargmann, Director, California Department of Developmental Services

o On occasion Director Bargmann was represented by Carla Castaneda,

Chief Deputy Director of Operations, California Department of

Developmental Services; and Dawn Percy, Deputy Director, Department

of Developmental Services

• Adam Dorsey, Program Budget Manager, California Department of Finance

• Brenda Grealish, Executive Officer, Council on Criminal Justice and Behavioral

Health, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Office of the

Secretary

o On occasion, Executive Officer Grealish was represented by Monica

Campos, Council on Criminal Justice and Behavioral Health, California

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Office of the Secretary

• Tyler Sadwith, Assistant Deputy Director, Behavioral Health, California

Department of Health Care Services

o On occasion Assistant Deputy Director Sadwith was represented by Jim

Kooler, Deputy Assistant Director, California Department of Health Care

Services; and Elise Devecchio-Cavagnaro, Consulting Psychologist,

California Department of Health Care Services

• Brandon Barnes, Sheriff, Sutter County Sheriff’s Office

o On occasion Sheriff Barnes was represented by Cory Salzillo, Legislative

Director, California State Sherriff’s Association

• John Keene, Chief Probation Officer, San Mateo County & President-Elect,

Chief Probation Officers of California

• Stephanie Regular, Assistant Public Defender, Contra Costa County Public

Defender Office & Co-Chair of the Mental Health Committee of the California

Public Defender Association

• Veronica Kelley, Director, San Bernardino County Department of Behavioral

Health & Board President, California Behavioral Health Directors Association

o On occasion, Director Kelley was represented by Michelle Cabrera,

Executive Director, California Behavioral Health Directors Association

(CBHDA)

• Farrah McDaid Ting, Senior Legislative Representative, Administration of

Justice, California State Association of Counties (CSAC)

o On occasion Josh Gauger, Legislative Representative, California State

Association of Counties (CSAC) also represented CSAC

• https://www.chhs.ca.gov/home/committees/ist-solutions-workgroup/

5

• Scarlet Hughes, Executive Director, California Association of Public

Administrators, Public Guardians and Public Conservators

• Jessica Cruz, Executive Director, National Alliance of Mental Illness – California

• Pamila Lew, Senior Attorney, Disability Rights California

o On occasion, Kim Pederson, Senior Attorney, represented Disability

Rights California

• Francine Byrne, Judicial Council of California

• Jonathan Raven, Chief Deputy District Attorney, Yolo County

II. Incompetent to Stand Trial Crisis – a History

Overview

Over the last decade, the State of California has seen significant year-over-year growth

in the number of individuals charged with a felony offense who are found Incompetent to

Stand Trial (IST) and committed to the State Department of State Hospitals (DSH) for

competency restoration services. The State of California has responded to the

substantial growth in the felony IST population through multiple investments to increase

DSH’s capacity to serve these individuals with serious mental illness. However, the

growth in the felony IST patients has exceeded the capacity and outpaced other efforts

to respond to the growth in the felony IST population, resulting in growing waitlist and

wait times to admission. In 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union sued DSH

(Stiavetti v. Ahlin

1

) regarding the amount of time IST defendants were waiting for

admission into a DSH treatment program alleging violations of individuals’ due process

rights. The Alameda Superior Court ultimately ruled that DSH must commence

substantive treatment services in 28 days for felony IST patients. DSH appealed this

ruling and ultimately in the summer of 2021, the Superior Court’s order was affirmed.

Meanwhile, the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has significantly exacerbated DSH’s

ability to meet the IST demands and as of November 2021 over 1,700 individuals are

awaiting restoration of competency treatment.

The IST Process

IST defendants are determined by a court to be unable to participate in their trial

because they are not able to understand the nature of the criminal proceedings or assist

counsel in the conduct of their defense. When the court finds a felony defendant

incompetent to stand trial in California, they can be committed to DSH to provide clinical

and medical services with the goal of restoring their competency and enabling them to

return to court to resume their criminal proceedings.

As court proceedings in a defendant’s trial are beginning, the defense attorney may

raise a doubt with the court that the defendant may be incompetent (doubt can also be

1

As of 12/01/2021 this case will be renamed Stiavetti v. Clendenin

6

raised by the prosecution and by the court itself). Once a doubt is declared, the court

will order an independent evaluation of the defendant by a court-appointed psychiatrist

or psychologist (also known as an Alienist). If the alienist finds that the individual is

incompetent, the court defers the current legal proceedings and orders a placement

evaluation by the CONREP Community Program Director to determine if the felony IST

should be treated in a DSH inpatient facility or an outpatient program.

The focus of treatment for the IST population is on restoration of trial competency in the

most expeditious manner so that the deferred legal proceedings can resume, not to

establish long-term mental health treatment for an individual. To this end, the training of

criminal procedures is continuously the focus of the treatment milieu for IST

patients. Once specific mental health issues and medication needs are addressed,

patients are immersed in groups or individualized sessions that train them in various

aspects of court proceedings. Each patient receives instruction as to what they are

charged with, the pleas available, the elements of a plea bargain, the roles of the

officers of the court, the role of evidence in a trial, and their constitutional

protections. Knowledge of these areas is assessed using a competency assessment

instrument. Additionally, an IST patient may participate in a mock trial where staff

members act as judge, jury, district attorney, and defense attorney to assess the

patient’s ability to work with counsel. At any point during the treatment program, the

patient may be evaluated to confirm they are competent to stand trial. After evaluation, if

there is concurrence that the patient is competent, a forensic report is sent to the court,

identifying that the patient is competent and ready to stand trial. Because the focus of

IST treatment programs is the rapid restoration of competency for the purposes of

criminal proceedings, individualized, comprehensive treatment of patients’ mental health

disorders is not provided by this treatment pathway.

National Data and California Data

The exponential increase in individuals found IST across the country has left State-run

mental health systems, including the California Department of State Hospitals (DSH),

challenged to meet the demands of year-over-year increases in the number of IST

referrals to their systems. A 2017 study conducted by the National Association of State

Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute (NRI)

2

found that from 1999 to

2014, the overall number of forensic patients in state hospitals increased by 74% while

the number of IST patients increased by 72% during that same period. The following

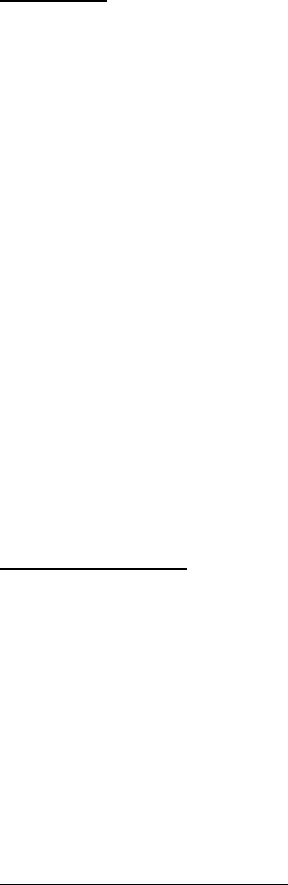

chart displays the percentage change overtime for 26 states:

2

Wik, A., Hollen, V., Fisher, W.H. (2017) Forensic Patients in State Psychiatric Hospitals: 1999-2016.

https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/TACPaper.10.Forensic-Patients-in-State-Hospitals_508C_v2.pdf.

7

Multiple state hospital systems across the country are facing lawsuits because of their

inability to continuously increase the number of forensic inpatient beds available to

admit and treat IST patients within court mandated timeframes, including here in

California (Stiavetti v. Ahlin) which has set a 28-day post commitment deadline for DSH

to begin substantive treatment of an IST ordered to DSH. Most notably, in the State of

Washington (Trueblood v. Washington (2015)), the State has paid over $100,000,000 in

contempt fines because of its inability to meet court ordered timeframes for admission

into treatment programs largely because the demand for IST services has outpaced the

state’s efforts to develop capacity

3

. Under a recent change to the settlement

agreement, the fines are being redirected to support improved access to appropriate

behavioral health services that are designed to dramatically reduce the number

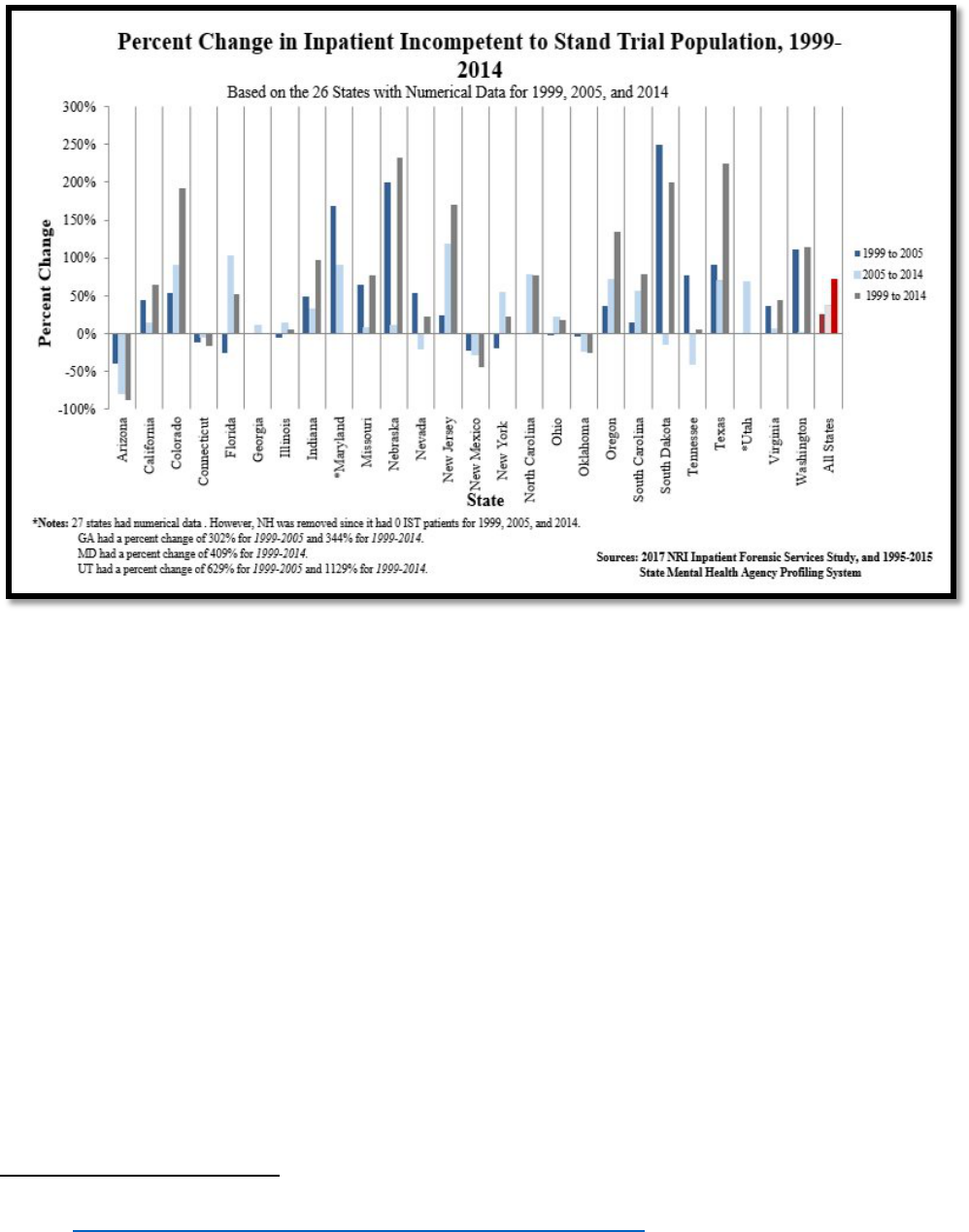

of people entering the criminal court system. However, as the following chart shows, as

Washington State has built out its forensic system in response to this suit, the referrals

3

From “Trueblood et al v. Washington State DSHS,” by Washington State Department of Social and Health

Services, https://www/dsjs/wa/gov/bha/trueblood-et-al-v-washington-state-dshs

. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

8

of IST patients have only continued to increase and, regardless of the funding made

available to the state system, capacity cannot keep up with demand

4

:

Unfortunately, the IST crisis in California has mirrored the crisis experienced across the

country. However, the size of California’s population has magnified the IST crisis in this

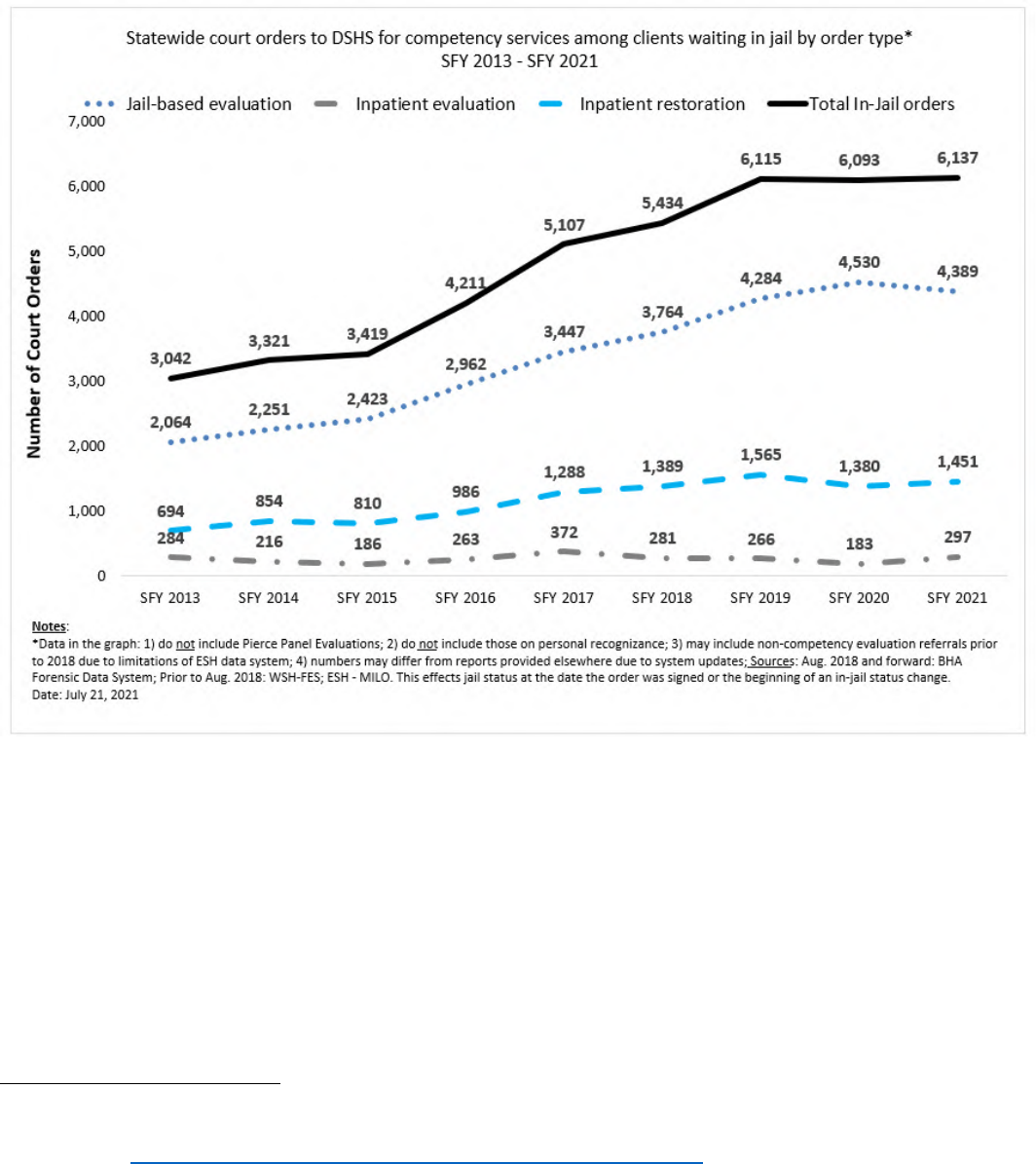

state. DSH first noted a substantial increase in IST referrals around 2013. Each year

since then, DSH has experienced growth in the number of IST referrals to the

department’s felony IST programs that has outpaced DSH’s efforts to increase capacity

to meet the demand for services resulting in a growing waitlist as displayed in the

following graph:

4

Chart displays growth in competency referral rates received by the Washington State Department of Social and

Health Services. From “Trueblood et al v. Washington State DSHS,” by Washington State Department of Social and

Health Services, https://www/dsjs/wa/gov/bha/trueblood-et-al-v-washington-state-dshs

. Retrieved November 22,

2021.

9

In 2020, while IST referrals decreased due to the global COVID-19 pandemic and

statewide Stay-in-Place orders, the IST treatment programs’ ability to admit new IST

patients were also significantly impacted by COVID-19 outbreaks and the necessary

infection control procedures implemented to protect patients and staff. In 2021-22, DSH

is again experiencing a high number of referrals from the courts that exceeds the pre-

pandemic referral rates, however, DSH must still maintain its implementation of COVID-

19 infection control practices as required by the California Department of Public Health.

These infection control measures as well as intermittent COVID-19 outbreaks continue

to limit the efficiency and the rate of admissions to its programs. As such, the waitlist

has grown to over 1700 individuals as of November 2021.

Individual Patient Characteristics

To better understand what was potentially driving the sustained increase in felony IST

referrals, DSH partnered with the University of California, Davis to study the IST

patients being admitted to Napa State Hospital. This review of DSH IST admissions

found the following:

• Between calendar years 2009 and 2016, the percent of IST patients admitted to

Napa State Hospital diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, psychosis NOS, or

mood disorder ranged from 72.5% to 84.1%. A small percentage of IST patients

were found to have a primary substance use disorder, cognitive disorder, or were

malingering.

• In 2009, 17.7% of IST patients admitted to Napa State Hospital had 16 or more

prior arrests. By 2016, the percentage of IST patients admitted to Napa State

Hospital with 16 or more prior arrests had increased to 46.4%.

• In 2016, approximately 47% of IST patients admitted to Napa State Hospital were

unsheltered homeless prior to their arrest. Between 2018 and 2020, 65.5% of

IST patients admitted to Napa State Hospital were homeless (sheltered or

unsheltered) prior to arrest.

10

• On average, 47% of IST patients admitted to Napa State Hospital had received

no Medi-Cal billable mental health services in the six months prior to arrest; 23%

had received one to two mental health services in emergency departments

(EDs); 20% had received three or more mental health ED services; and 10%

received no mental health ED services.

To provide some context to these findings, DSH and UC Davis conducted a national

survey asking state mental health officials about their states’ crisis. The responses

received were another indicator of the scale of the problem facing the nation: 68.8% of

survey respondents indicated the rate of referrals for competency restoration for

misdemeanor offenses was increasing in their state, 65.3% of respondents indicated

that the rate of referrals for competency restoration for felony offenses was increasing in

their state, and 78% of respondents indicated the rate of referrals for competency

restoration for felony and misdemeanor offenses were both increasing in their state. In

addition, 70.8% of respondents shared that their state hospital system has a waitlist for

admitting IST patients and 38.8% of respondents indicated that their state is currently

facing litigation related to the admission of IST patients into their system of care. Finally,

the survey asked respondents to rank what, in their experience, were the leading

causes of this crisis. Here are the top four responses ranked in order of impact to the

crisis:

• Inadequate general mental health services

• Inadequate crisis services in community

• Inadequate number of inpatient psychiatric beds in community

• Inadequate ACT services in community

The results of this national survey and the clinical review of the IST patients admitted to

DSH has led DSH to hypothesize that the drivers of this crisis are as follows:

• Individuals with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders are drifting into an untreated,

unsheltered condition.

• These conditions are leading to increased contact with police and

criminal charges.

• This increased contact is leading to a surge in IST referrals to state hospitals.

• Building more state hospital beds will only exacerbate the problem long term.

• IST restoration of competency treatment is not an adequate long-term treatment

plan.

Finally, DSH wanted to know if currently designed IST treatments impact or change the

trajectory of IST patients’ lives subsequent to discharge from DSH. DSH worked with

the California Department of Justice (DOJ) to obtain criminal offender record information

11

for IST patients discharged from DSH. The offender record information was then

matched with DSH discharge data and used to determine disposition outcomes for the

original IST commitment as well as to determine the rates of recidivism of individuals

post competency restoration at DSH. The analysis of DOJ and DSH data reflects how

the treatment provided by law to IST patients to restore competency does not have a

long-term positive impact for the individual and the community. Under existing law,

competency treatment is focused on the stabilization of an individual’s psychiatric

symptoms and basic legal education which together are intended to allow the defendant

to work with their attorney, understand the charges against them, and effectively

participate in their own defense.

DSH looked at the 3-year post discharge recidivism rates utilizing DOJ criminal offender

record information data and found a:

• 69% recidivism rate

5

for IST patients discharged from DSH in FY 2014-15

• 72.3% recidivism rate for IST patients discharged from DSH in FY 2015-16

• 71% recidivism rate for IST patients discharged from DSH in FY 2016-17

In examining the legal pathways of IST patients post competency restoration treatment

at DSH state hospitals and jail-based competency treatment programs, the data shows

that from FY 2016-17 through FY 2018-19 (6,048 IST discharges in total), 15% of felony

IST patients had a single offense and post discharge from DSH 35% had their charges

dropped (includes case dismissed, proceedings suspended, not guilty, acquitted). Over

the same period, 85% of felony IST patients had multiple offenses and post discharge

from DSH 24% had some or all their charges dropped. The full range of disposition

outcomes for the felony IST patients discharged over this period include the following:

27.8% were sentenced to jail/probation (served either concurrently or consecutively),

25.9% had their cases dismissed, 24.3% were sentenced to prison, 14.2% were

sentenced only to jail and 0.2% were found guilty of some or all of their charges but

found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGI) and committed to DSH for treatment rather

than prison.

In summary, what this analysis shows is that most individuals committed to DSH as an

IST are not sentenced to state prison or committed to DSH for longer-term treatment.

Most IST patients restored by DSH return to their county of commitment and serve time

in jail, are released on probation, or are simply released. The rate of arrests of

discharged IST patients shows that whatever circumstances led to an individual’s prior

arrest have likely not changed and most IST patients are stuck looping through the

criminal justice system and DSH.

5

Recidivism rate reflects percentage of individuals with new arrests after discharge from DSH. DSH focuses on

arrests instead of convictions because defendants are committed to DSH post-arrest but pre-conviction.

12

III. Department of State Hospitals’ Efforts to Date

Since FY 2012-13, DSH has made multiple efforts to mitigate the effects of increasing

IST referrals through capacity expansion, system improvements, and legislative

changes.

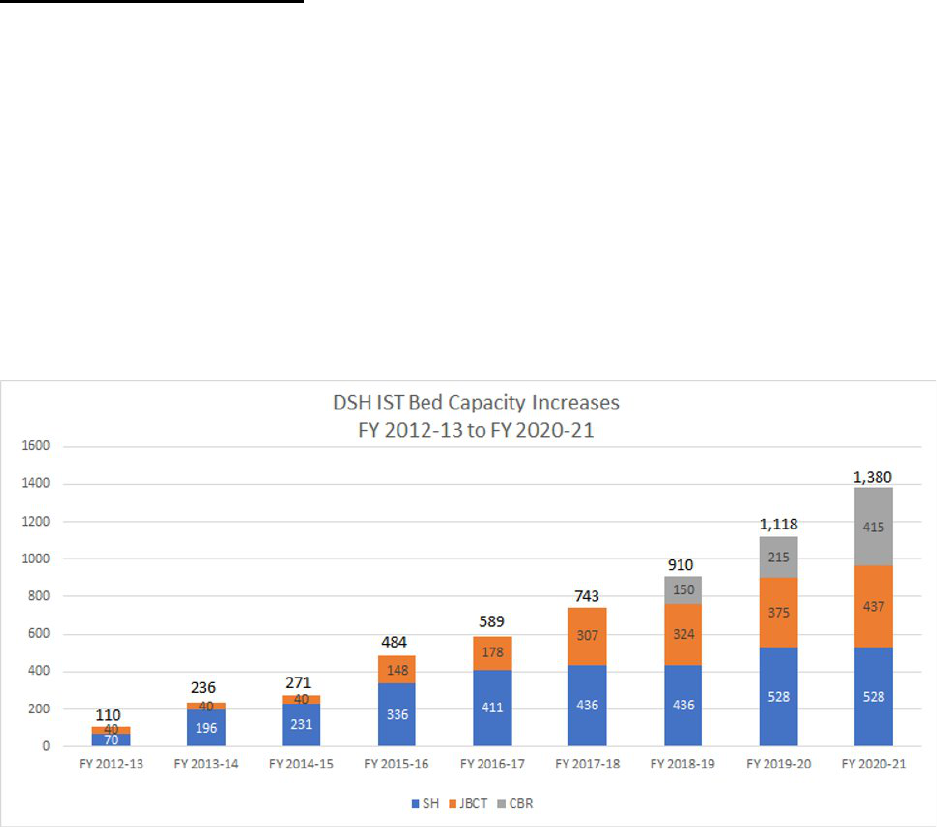

Increased Capacity at DSH

Since the beginning of the IST crisis, DSH has established new IST capacity through

the activation of 528 new state hospital beds, 445 jail-based treatment beds, 415

community-based restoration (CBR) beds, and a 78-bed Conditional Release Program

(CONREP) step down program (currently in progress). DSH is also in the process of

establishing 352 additional CBR beds and a CONREP Mobile Forensic Assertive

Community Treatment (FACT) Team to further expand DSH’s capacity to serve IST

patients. As the following table shows, in the first year of the crisis DSH added 110 beds

for IST treatment and by FY 2020-21 DSH had added a total of 1,380 beds between

State Hospitals (SH), Jail Based Competency Treatment (JBCT) programs, and the

Community Based Restoration (CBR) program:

In the 2021-22 budget, DSH was appropriated $255 million to create new sub-acute

capacity across the state to serve felony IST patients; $32.8 million to expand the CBR

program by 552 beds (300 in LA, of which 200 activated in spring 2021, and 252 across

the rest of the state); $47.6 million to expand the DSH Felony Mental Health Diversion

(Diversion) program (see pp. 17-18 for a detailed description of this program); $13.1

million to expand the department’s Jail Based Competency Treatment program

expansion and; $9.7 million to establish a Forensic Assertive Community Treatment

13

(FACT) program in CONREP to serve higher acuity patients, such as ISTs, in the

community.

In this budget, DSH also received $12.7 million to establish a four year, limited-term IST

Re-evaluation Program. This program establishes a temporary team of forensic

evaluators who will re-evaluate IST patients for competency who have been committed

to DSH and have been in jail for over 60 days. If an IST is evaluated and found to have

regained competency while in jail the IST Re-evaluation team will submit the

appropriate reports to the courts. Additionally, if the IST Re-evaluation identifies an IST

who has not restored to competency may be appropriate for the DSH Felony Mental

Health Diversion program or community-based restoration, the IST Re-evaluation team

can make a referral to these programs. The goal of this program is to address the

current waitlist of over 1,700 IST patients by bridging the gap between DSH’s current

capacity, the current rate of IST referrals, and the ongoing impacts of COVID-19 to

admissions and discharges to the State Hospitals while the department’s new

investments in community-based treatment are implemented.

As part of its efforts to increase the number of felony IST patients that receive treatment

each year, the Department contracts with 21 California counties to provide restoration of

competency services to IST patients in county jail facilities. Jail-Based Competency

Treatment (JBCT) programs are designed to treat IST patients with lower acuity and to

quickly restore them to trial competency, generally within 90 days. If a JBCT program is

unable to restore an IST patient to trial competency quickly, the patient can be referred

to a state hospital for longer-term IST treatment. DSH currently operates three JBCT

program models:

1. Dedicated bed model – serves IST patients from one specific county with an

established number of dedicated program beds.

2. Regional model - serves IST patients from multiple counties statewide with an

established number of dedicated program beds.

3. Small county model – serves 12 to 15 IST patients annually and does not have

dedicated program beds.

Funding for these programs includes patients’ rights advocacy services. The funding for

the patients’ rights advocacy services complies with Assembly Bill (AB) 103 (Statutes of

2017). AB 103 requires that all DSH patients have equal access to patients’ rights

advocacy resources, including IST patients who are admitted to JBCT programs.

Over the last few fiscal years, the Department has also focused efforts on expanding

the capacity of its CONREP program with the goal of stepping down more patients

committed to DSH as NGI or as Offenders with Mental Health Disorders (OMDs) to free

up additional beds within the State Hospitals for IST patients. CONREP is DSH’s

statewide system of community-based services for specified court-ordered forensic

individuals. Mandated as a State responsibility by the Governor's Mental Health

14

Initiative of 1984, the program began operations on January 1, 1986 and operates

pursuant to statutes in Welfare and Institutions Code (WIC) 4360 (a) and (b). The goal

of CONREP is to promote greater public protection in California’s communities via an

effective and standardized community outpatient treatment system. The CONREP Non-

Sexually Violent Predator (Non-SVP) population includes:

• Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity (NGI) (Penal Code (PC) 1026)

• Offender with a Mental Health Disorder (OMD) (both PC 2964 parolees who have

served a prison sentence and PC 2972 parolees who are civilly committed for at

least one year after their parole period ends). This category also includes the

Mentally Disordered Sex Offender (MDSO) commitment under WIC 6316

(repealed).

• Felony Incompetent to Stand Trial (IST) (PC 1370 patients who have been court-

approved for outpatient placement in lieu of state hospital placement)

Individuals suitable for CONREP may be recommended by the state hospital Medical

Director to the courts for outpatient treatment. Currently, DSH contracts with seven

county-operated and eight private organizations to provide outpatient treatment services

to non-Sexually Violent Predator clients in all 58 counties of the state.

DSH is partnering with several community-based providers to build out the continuum of

care and increase the availability of placement options dedicated to CONREP clients.

This expands the number of community beds available for patients who are ready for

outpatient treatment but still need a higher level of care within CONREP. These facilities

allow patients to step down into a lower restrictive environment and focus on the skills

necessary for independent living when transitioning to CONREP. The expansion of

CONREP capacity and patient placement allows DSH to backfill vacated state hospital

beds with pending IST placements who are not eligible for outpatient treatment.

Expanding the availability of beds to treat DSH patients is critical to providing timely

access to those requiring and awaiting treatment in higher acuity state hospital settings.

Current efforts in expanding residential placement options include:

• Authority to establish a dedicated 78-bed step-down program intended to address

higher-level needs and patient acuity and operated in a secured Institute for Mental

Disease (IMD) facility. The program was designed for state hospital patients ready

for CONREP in 18-24 months. This setting allows for OMD and NGI patients to

step down into a lower restrictive environment and provide the skills necessary for

a more independent living setting when transitioning to CONREP, thereby allowing

for the vacated state hospital beds to be backfilled by IST patients. This program

is pending official regulatory approval and necessary modifications to the facility

but is expected to be activated in late summer 2022.

• Recognizing the need for more step-down CONREP beds in northern California,

DSH received authority to partner with a new provider to establish a 10-bed IMD

15

program. Activation began in July 2020 and was expanded by an additional 10

beds in July 2021.

• Authorized in 2021 Budget Act, DSH received authority to partner with a provider

to establish a 180-bed Forensic Assertive Community Treatment (FACT) model of

care in CONREP that will provide 60 beds each in Northern California, Southern

California, and the Bay Area. This new level of care for CONREP will establish

residential beds where services will be delivered onsite allowing for placement of

individuals with higher needs. The program is designed to provide 24/7 services to

clients as needed to support client success and reduce the likelihood of

rehospitalization through de-escalation and crisis intervention practices.

Additionally, a FACT model of care can be used to place IST patients ordered to

CONREP where a community-based restoration program is not available. DSH

estimates program activation of the 60 Northern CA beds to occur in January 2022,

the 60 Southern CA beds to activate in early spring 2022, and the 60 Bay Area

beds to activate in early winter 2022.

• An augmentation of $1 million in the 2019 Budget Act to support general housing

costs being absorbed by CONREP providers.

Systems Improvements

The second strategy DSH has employed in its attempt to manage the escalating IST

crisis has been the implementation of multiple systems improvements that increase

DSH’s efficiency in admitting, treating, and discharging IST patients. Through these

efforts, the department has reduced the average length of stay (ALOS) for IST patients

to 148.7 days in a state hospital bed and 69.7 days in a jail-based competency bed. The

decrease in the ALOS for IST patients is the result of improved utilization management

at the state hospitals (a process by which treatment is matched to a patient’s specific

clinical needs), the creation of the Patient Management Unit, and multiple legislative

changes that supported each of these efforts.

The Patient Management Unit (PMU) was established in June 2017 in the Welfare and

Institutions Code 7234 through Assembly Bill 103 (Chapter 17, Statutes of 2017) to

provide centralized management, oversight, and coordination of the referral and patient

pre-admission processes to ensure placement of patients in the most appropriate

setting based on clinical and safety needs. Prior to the establishment of the PMU, the

court system was able to order commitments to any DSH hospital of its choosing,

creating admission backlogs and inefficiencies. Now, PMU receives all court

commitments to the department and utilizes DSH’s Patient Reservation Tracking

System (PaRTS) to manage the admissions of all DSH patients.

Finally, multiple legislative changes have been made to support the department’s efforts

to maximize the use of each DSH-funded bed:

• AB 2186 (Chapter 733, Statutes of 2014) – Involuntary Medication Orders and

Court Reports

16

o Amended the law to require courts to reassess the authorization of

Involuntary Medication Orders (IMOs) upon the filing of the initial

competency progress report and any ongoing progress reports to the court

and that a petition may be filed within 60 days of the expiration of the one-

year IMO. This change created efficiency and consistency in the

application for and use of IMOs at DSH. The use of medications is a core

component of the treatment of IST patients

• AB 2625 (Statutes of 2014) – Unlikely to Regain Competency and Unrestored

Defendants – 10 Days to Return to Court

o Amended the law to require that IST patients who are determined to be

unlikely to restore to competency be returned to court within 10 days and

required that IST patients who had been committed to DSH up to the

maximum time allowed by law (in 2014, the maximum length of

commitment to DSH for an IST defendant was 3 years) to be returned to

court 90 days prior to the expiration of their commitment. This change

was intended to help DSH discharge patients more quickly so additional

IST patients could be admitted into the system, increasing the number of

IST patients that could be treated per year.

• AB 1810 (Statutes of 2018) – Prevents Transfer of Competent Defendants to

DSH

o Amended the law to allow courts to order a re-evaluation of an

IST defendant pending transfer to a State Hospital if they receive

information from the jail treatment provider or defendant’s counsel that the

defendant may no longer be incompetent. DSH found that a significant

number of IST patients committed to DSH had regained competency prior

to admission to DSH; this change was intended to prevent the transport

and admission of IST patients who had regained competency and

maintain limited DSH resources for those who were still IST.

• SB 1187 (Statutes of 2018) - Reduced the maximum length of stay for felony IST

patients from 3 years to 2 years.

o Amended the law to reduce the maximum commitment of IST patients to

DSH from 3 years to 2 years. This change was intended to discharge

patients from limited DSH beds more expeditiously to admit additional IST

patients and increase the potential number of IST patients served in a

year.

• Assembly Bill 133 (Statutes of 2021) – Misdemeanor IST Patients and Charges

for Non-Restorable IST Patients

o Amended the law to remove DSH as a county placement option for IST

patients with misdemeanor charges to preserve all appropriate state

17

hospital beds for felony IST patients. Also amended law to charge

counties a daily bed rate for IST patients that have been found non-

restorable that are not transported from DSH by the county within the

statutorily required 10-day timeframe.

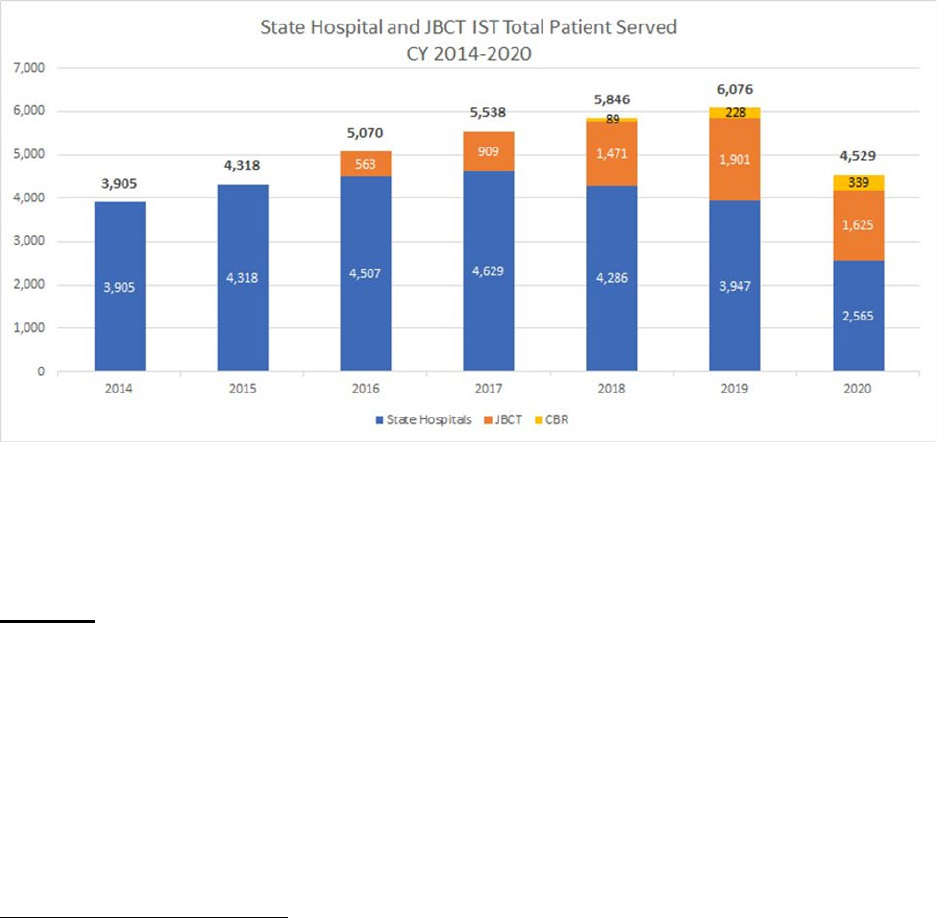

Each of these systems improvements has helped DSH reduce the length of stay of IST

patients in a DSH bed and, in conjunction with the capacity DSH has added to its

system of care, allowed the department to increase the number of IST commitments

served year-over-year

6

:

However, the demand for IST treatment has continued to outpace all efforts to create

enough capacity and system efficiency to reduce the number of IST patients pending

placement to DSH and reduce the length of time between commitment to the

department and receipt of substantive competency treatment.

Demand

By FY 2017-18, DSH recognized that the demand for IST treatment services was not

going to be met by capacity created within the State Hospital system. At this time the

department began working to establish treatment pathways in the community with the

long-term goal of decreasing demand for State Hospital services by connecting more

people with Serious Mental Illness into ongoing community care. The Budget Act of

2018 included funding for two major new programs to help DSH realize this vision.

The Budget Act of 2018 allocated $13.1million for DSH to contract with the Los Angeles

County Office of Diversion and Reentry (ODR) for the first community-based restoration

6

The table below, “State Hospital and JBCT IST Total Patients Served” reflects a drop in total patients served in

2020; this anomaly was caused by the SARS COVID-19 pandemic. State Hospitals ability to admit and discharge

patients during the first twelve months of the pandemic was significantly limited by necessary infection-control

measures taken by the Department to protect patients and staff in its congregate living treatment environment.

18

(CBR) program in the state. In this program, ODR subcontracts for housing and

treatment services for IST patients in the community. Most IST patients in this program

live in unlocked residential settings with wraparound treatment services provided on

site. The original CBR program provided funding for 150 beds; investments in the LA

program since 2018 has increased the program size to 515 beds. In addition, DSH has

received funding to implement additional CBR programs across the state. The Budget

Act of 2021 included ongoing funding to add an additional 252 CBR beds in counties

outside of Los Angeles, bringing the total number of funded CBR beds to 767.

The Budget Act of 2018 also allocated DSH $100 million (one-time) to establish the

DSH Felony Mental Health Diversion (Diversion) pilot program. Of this funding, $99.5

million was earmarked to send directly to counties that chose to contract with DSH to

establish a pilot Diversion program (the remaining $500,000 was for program

administration and data collection support at DSH). Assembly Bill 1810 (2018)

established the legal (Penal Code (PC) 1001.35-1001.36) and programmatic (Welfare &

Institutions Code (WIC) 4361) infrastructure to authorize general mental health diversion

and the DSH-funded Diversion program. The original Diversion pilot program includes

24 counties who have committed to serving up to 820 individuals over the course of

their three-year pilot programs. In FY 2021-22, DSH received additional funding to

expand this pilot program as follows:

• $17.4 million to expand current county contracts by up to 20%; WIC 4361

updated to require any expansion be dedicated to diverting defendants who

have been found IST by the courts and committed to DSH

• $29.0 million to implement diversion programs in any other county interested in

contracting with DSH

The goal of both the CBR and Diversion programs is to demonstrate that many of the

individuals committed to DSH as IST patients can be treated effectively and safely in the

community. Since launching these programs in 2018, DSH has partnered with some of

the most preeminent authorities in the treatment of individuals with Serious Mental

Illnesses and criminal justice involvement to provide technical assistance and training

for counties across the state implementing a DSH Diversion program and has shared

many of those resources with all counties, regardless of their participation in the DSH

program, through the Diversion program’s public webpage:

https://www.dsh.ca.gov/Treatment/DSH_Diversion_Program.html

Since 2018, DSH has provide over 100 hours of free training and technical assistance

to counties and continues to build out the resources it has to offer as the CBR and

Diversion programs grow. As of June 30, 2021, counties participating in the Diversion

pilot had diverted 458 individuals (some had been found IST and some were defendants

the county determined to be likely-to-be IST) and the Los Angeles CBR program had

served 641 IST patients.

19

IV. IST Solutions Workgroup Process

In accordance with Assembly Bill 133 and the 2021 Budget Act, the California Health

and Human Services Agency (CalHHS) and DSH established a statewide IST Solutions

Workgroup in August 2021. The IST Solutions Workgroup members were appointed by

CalHHS Secretary Mark Ghaly and the composition of the Workgroup, as required in

statute, included representatives from several state agencies, the Judicial Council, local

government and criminal justice system representatives, and representatives of IST

patients and their family members.

This Workgroup met five times (8/17/2021, 8/31/2021, 10/12/2021, 11/5/2021,

11/19/2021) as part of the IST solutions development process. To advance the

development of short-, medium-, and long-term strategies, three sub-working groups

were established that focused on specific areas of opportunity (See Appendix A for a full

list of working group members). All three groups were called on to focus all

recommendations of short-term solutions on the individuals currently on the waitlist.

These three working groups generated strategies for consideration by the full IST

Solutions Workgroup for inclusion in the final report to CalHHS and DOF. The three

topic-focused working groups included:

Working Group 1: Early Access to Treatment and Stabilization for Individuals

Found Felony IST

The goal of Working Group 1 was to identify short-term solutions to provide early

access to treatment and stabilization in jail or via Jail Based Competency Treatment

(JBCT) programs to maximize re-evaluation, diversion or other community-based

treatment opportunities and reduce IST length-of-stay in jails. Working Group 1 met on

9/21/2021, 9/28/2021, and 10/26/2021.

Working Group 2: Diversion and Community-Based Restoration for Felony ISTs

The goal of Working Group 2 was to identify short, medium, and long-term strategies to

maximize the implementation of IST Diversion and Community-Based Restoration

(CBR) programs across the state. Working Group 2 met on 9/24/2021, 10/1/2021, and

10/22/2021.

Working Group 3: Initial County Competency Evaluations

The goal of Working Group 3 was to identify solutions to reduce the overall number of

individuals found IST by strengthening the quality of the initial competency evaluations

ordered by the courts (also known as alienist evaluations). Working Group 3 met on

9/17/2021, 9/24/2021, and 10/15/2021.

Due to COVID restrictions and the tight time frame of the process, meetings were held

virtually using Zoom technology that enabled full participation of all members, as well as

the public, who were routinely invited to comment using the Zoom “chat” feature, as well

20

as verbally as time permitted. The goal was to establish a transparent and inclusive

process that allowed active participation from a diverse spectrum of participants. All

meetings followed the requirements of the Bagley-Keene Open Meeting Act.

Meeting agendas, presentations, written input from members and the public, responses

to information requests, and meeting minutes from the IST Solutions Workgroup and the

three topic-focused working groups are available on the IST Solutions Workgroup web

site.

Guiding Principles for Generating Recommendations

The statute provided guidance for what the IST Workgroup solutions should focus on

when generating solutions to the IST crisis. This guidance included:

1. Reduce the total number of felony defendants determined to be IST

2. Reduce the lengths of stay for felony IST patients

3. Support felony IST defendants to receive early access to treatment before

transfer to a restoration of competency treatment program to achieve stabilization

and restoration of competency sooner.

4. Support increased access to felony IST diversion options.

5. Expand treatment options for felony IST individuals, such as community-based

restoration programs, jail-based competency treatment programs, and state

hospital beds.

6. Create new options for treatment of felony IST defendants including community-

based, locked, and unlocked facilities.

7. Establish partnerships to facilitate admissions and discharges to reduce

recidivism and ensure that the most acute, high-risk, and at need patients receive

access to State Department of State Hospitals beds, while patients with lower

risk of acuity are treated in appropriate community settings.

In addition to this statutory guidance, the IST Solutions Workgroup adopted the

following guiding principles to frame its recommendations:

• Mental health treatment should be delivered in community-based treatment

options to the greatest extent possible.

• While jail is not the appropriate setting for mental health treatment, jails need to

be able to provide mental health treatment for individuals who are in jail and

require treatment.

• Engagement of individuals with lived experience and family members in planning

and implementing solutions and programs is critical.

21

• Short-term solutions focus on treating the 1700+ individuals found incompetent to

stand trial on felony charges and waiting in jail for access to treatment or

diversion programs.

• Medium-term solutions focus on increasing access to community-based

treatment and diversion for individuals found incompetent to stand trial on felony

charges.

• Long-term solutions aim for system transformation and to reverse the trend of

criminalizing mental illness.

• Implementing solutions to achieve the short-, medium- and long-term goals

requires collective, multi-sector solutions and collaboration.

• To address the current IST crisis, implementation of short-term strategies that

are not in alignment with long-term goals may be needed, but should be time-

limited, phased out when medium- and long-term solutions are implemented, and

not detract from the focus and implementation of the long-term goals.

Process for Synthesizing Recommended Solutions

Over the course of the topic-focused working group meetings, more than 100 potential

solutions were generated by members and the public through an iterative process of

idea generation, reflection, and refinement within each of the three working groups, as

well as the larger Workgroup. Additionally, these solutions were assessed to determine

which were most feasible, actionable, and relevant to addressing the short-, medium-,

and long-term timeframes and goals, which enabled the team to reduce and consolidate

the total number of potential solutions from 100 to ~35. Any recommendation that did

not represent an actionable solution was not included. A draft compilation of the

solutions was presented to the full workgroup for discussion. Through that discussion

and additional solutions submitted from workgroup members and other organizations

and members of the public who participated in the meetings, a final list of 41

recommended solutions was generated to be presented to the CalHSS and DOF.

22

V. Census of Recommended Solutions from the IST Workgroup Meetings for Submission to CalHHS and

Department of Finance

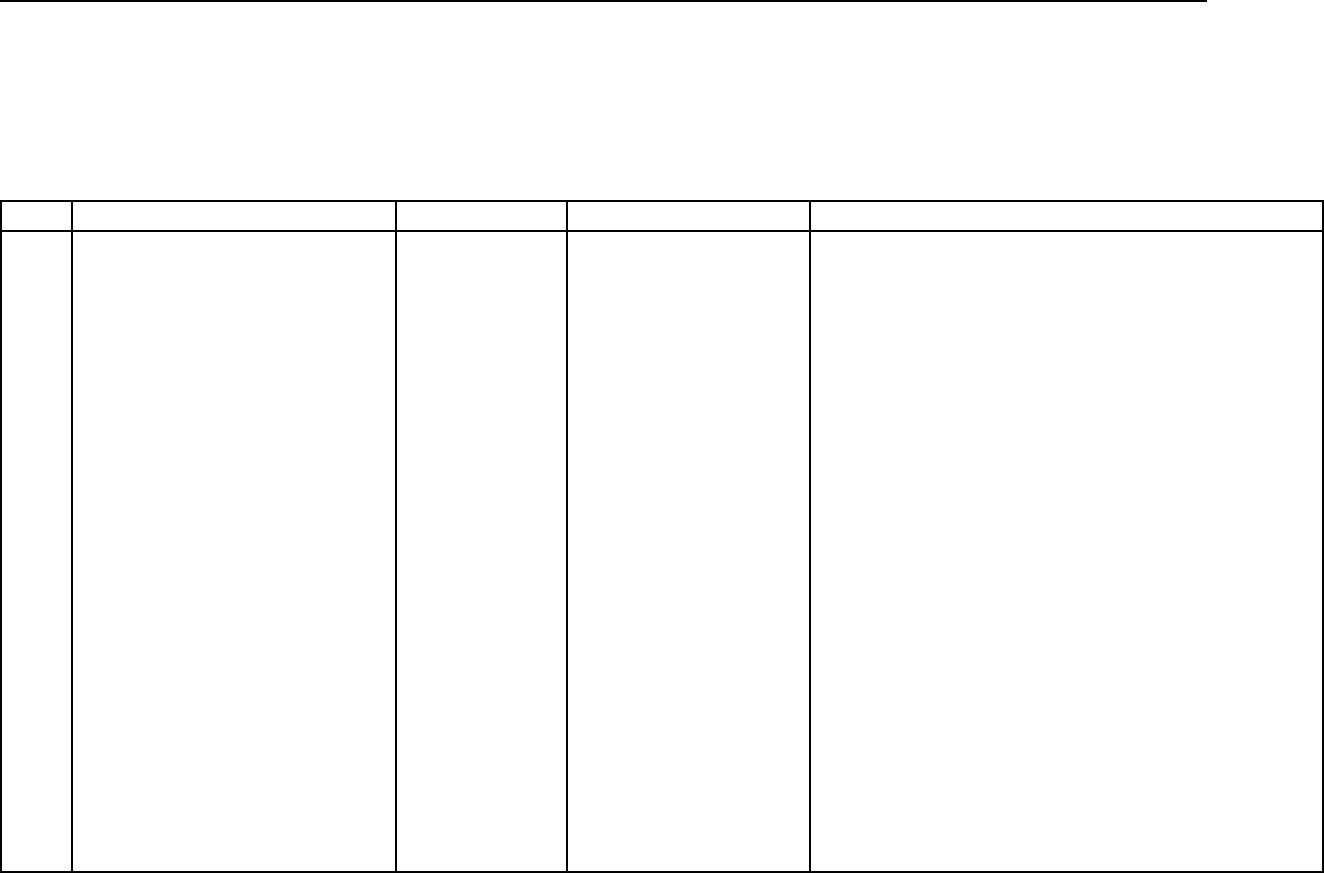

Short Term Strategies: Solutions that can begin implementation by April 1, 2022

Goals:

a. Provide immediate solutions for 1700+ individuals currently found incompetent to stand trial on felony charges and

waiting in jail for access to a treatment program.

b. Provide quick access to treatment in jail, the community, or a diversion program.

c. Identify those who have already restored.

d. Reduce new IST referrals.

#

Strategy

Type

Potential Impact

Other Considerations

S.1

Support increased access to

psychiatric care, including

stabilizing medications in jail

for felony ISTs while pending

transfer to other IST treatment

programs or when returning

from IST treatment programs

to jail pending court

proceedings, including:

• Provide funding to jails

to expand the use of

long-acting injectable

psychiatric medications

(LAIs) in jail settings.

• Use of

technology/telehealth

for jail clinicians to

access tele-

Funding/

Policy

Provides

opportunities for

faster stabilization of

mental health

symptoms in jail and

increase

opportunities for

individuals to be

candidates for

Diversion or

community-based

restoration

programs. While jails

are not the

recommended

treatment setting,

recognizes there is

an immediate crisis

Jails do not receive state funding support for

treatment and housing of individuals found

IST on felony charges unless they have been

admitted to a DSH-funded jail-based

competency treatment program. However,

individuals who have been deemed

incompetent to stand trial on felony charges

and are not yet transferred to a Diversion or

other treatment program should receive

appropriate mental health treatment until they

are transferred to a treatment program.

Funding to jails to support the resources and

costs to providing these services may also

need to be considered.

Jail formularies may need to be updated to

include long-acting injectable medications

(LAIs).

23

psychiatrists to provide

medication/treatment

determinations,

including involuntary

medications, when

necessary, ordered by

the court and

appropriate due

process procedures are

followed.

• Increase opportunities

to rapidly connect a

court-appointed

competency evaluator’s

opinion that a patient

needs medication to jail

providers for

consideration in an

individual’s treatment

plan.

• Support training

opportunities for jail

clinicians on patient

engagement, including

rapport building skills

and motivational

interviewing.

and responses must

address the crisis in

the short-term.

There is not

currently sufficient

community capacity

for stabilization of

acute mental health

conditions.

Individuals who are

currently waiting in

jail for admittance to

treatment programs

are more likely to

access treatment in

existing Diversion

and community-

based restoration

programs if their

acute mental health

symptoms are

rapidly stabilized.

Lack of symptom

stabilization has

been identified as

the primary barrier to

Department of State

Hospitals (DSH) IST

Diversion Program

placement.

S.2

Improve coordination between

State, criminal justice

Operations/

Funding

Increased

partnership and

Short-term bridge solutions may need to be

implemented to advance these solutions until

24

partners, county

behavioral/mental health

directors, and county public

guardians, for IST patients,

including:

• Transition/treatment

planning to ensure

continuity of care

between systems and

providers.

• Providing a 90-day

medication supply for

individuals discharging

to the community from

jail, Diversion, or

restoration of

competency treatment

programs.

• Use of common drug

formularies, wherever

possible.

• Data sharing/use of

business associate

agreements.

• Identifying community

based and Diversion

alternatives.

opportunities for

Diversion and

community-based

treatment for felony

ISTs. Increased

support for

transitions and re-

entry after felony IST

finding or release to

reduce

destabilization and

re-arrest.

the CalAIM reforms, addressing enrollment in

Medi-Cal prior to release and enhanced care

management, noted in Strategy L.2 are

implemented.

Individuals with mental illness, family

members, and advocates should be included

in stakeholder discussions about how best to

coordinate these efforts.

S.3

Provide training and technical

assistance and develop best

practice guides (toolkits) for

jail clinical staff, criminal

justice partners, boards of

supervisors, and county

Training

Increased early

treatment

engagement and

stabilization of

individuals will

reduce the

DSH Clinical Operations is actively providing

technical assistance and training, as well as

psychopharmacology consultation, to any

county partners who request it.

25

administrators for

understanding and

implementing effective

treatment engagement

strategies including:

• Seeking treatment and

medication histories

from family members.

• Utilization of incentives

and other strategies to

engage treatment

including best practices

for developing

patient/clinician

rapport, continuity, and

securing the voluntary

consent to medication

whenever possible.

• Obtaining involuntary

medication orders and

administering

involuntary

medications, when

necessary, ordered by

the court, and

appropriate due

process procedures are

followed.

symptoms of

psychosis such as

hallucinations,

delusions, and

disorganized

thinking. This will

provide increased

opportunity for

placement in

Diversion or

community-based

restoration

programs, as well as

decrease the length

of stay for individuals

on the pathway to

JBCT or State

Hospital placement.

This recommendation focuses primarily on

training and technical assistance needs.

Implementation of these strategies may

require funding or other support.

S.4

Re-assess the DSH current

waitlist, in partnership with

DSH, county behavioral

health, jail treatment

providers, and criminal justice

Operations

Reduce current

waitlist and increase

access to

community-based

The 2021 Budget Act included funding for

DSH to re-evaluate individuals on the IST

waitlist after 60 days to determine if an

individual has been restored to competency

or stabilized enough to be considered for

26

partners to identify individuals

who may be eligible for

release into community

treatment programs such as

MH Diversion, DSH IST

Diversion, CONREP or

community-based restoration,

address medication/treatment

needs to stabilize mental

health symptoms in jail,

identifying individuals who,

due to their psychiatric acuity,

may need priority transfer to a

state hospital pursuant to

California Code of

Regulations Section 4177,

and swiftly move individuals

into these programs to

maximize their utilization.

treatment for felony

ISTs.

Diversion or CONREP placement. Further

opportunities exist to actively partner with

counties prior to 60 days to identify

individuals who may be candidates for

placements in Diversion/CONREP.

S.5

Expand technical assistance

for Diversion and community-

based Restoration, including:

• Developing best

practice guides in

partnership with key

stakeholders.

• Providing training and

technical assistance to

newly developing

programs.

• Providing training and

technical assistance on

Training

Supports increased

utilization and

expansion of

Diversion and

community-based

treatment options for

felony ISTs.

DSH developed and implemented a Diversion

Academy for counties who plan to implement

DSH Diversion programs for ISTs. This was

offered in the fall 2021 to counties who have

applied for funding to establish new Diversion

programs. DSH also maintains a website of

technical assistance resources to support

Diversion. Additionally, DSH plans to expand

technical assistance opportunities to counties

to support implementation of community-

based restoration programs.

27

options to assess and

mitigate public safety

risks.

S.6

Provide training and technical

assistance for Court

appointed evaluators to

improve the quality of the

reports used by courts in

determining a defendant is

incompetent to stand trial:

• Develop checklists for

court appointed

evaluators to follow of

items to be considered

when making

competency

recommendations,

including American

Academy of Psychiatry

and the Law guidelines

and/or Judicial Council

rules of Court and

considering defense

counsel observations

and concerns regarding

their client’s ability to

participate rationally in

their defense.

• Develop template

evaluation reports that

include all checklist

items, including short-

form report options for

Training

Improves quality of

court-appointed

evaluator reports to

inform the court

whether an

individual may be

incompetent to stand

trial and the basis of

that determination

including an

individual’s

diagnosis, whether

they require an

involuntary

medication order

(IMO), or if they are

malingering

symptoms. May

reduce the number

of individuals found

incompetent to stand

trial and increase

access to treatment

and stabilization

when treatment

engagement is

difficult due to an

individual’s severe

symptoms of

psychosis.

This recommendation focuses primarily on

training and technical assistance needs.

Implementation of these strategies may

require funding or other support.

28

when clinically

appropriate

• Develop technical

assistance and training

videos to increase

knowledge and skills

for existing court

appointed evaluators,

including principles of

community based

mental healthcare,

which can be available

on DSH website.

• Ensure training and

technical assistance

includes information on

discrepancies and

biases in evaluations.

S.7

Prioritize community-based

restoration and Diversion by:

• Allowing individuals

placed into Diversion to

retain their place on the

waitlist should they be

unsuccessful in

Diversion and need

inpatient restoration of

competency services.

• Improving

communication

between DSH and local

courts in collaboration

Policy

Addresses concerns

from Diversion

providers that

individuals will not

have timely access

to a DSH treatment

program if the

individual’s mental

health symptoms

and community

safety risk

significantly

increases.

Additionally, reduces

DSH issued Departmental Letter 21-001 on

November 3, 2021, to implement this

recommendation. It outlines the process to

facilitate coordination between Diversion

programs, the courts, and DSH when an

individual is being considered for Diversion to

ensure the individual is not inadvertently

transferred to a DSH hospital or jail-based

competency treatment program. It also

establishes the procedure for a Diversion

program client to reenter the waitlist with their

original commitment date when an individual

is revoked from Diversion and needs to be

transferred into a secure treatment program.

29

with the Judicial

Council so that a

person on the waitlist is

not removed from

Diversion consideration

prematurely when a

bed becomes available

at DSH.

instances where

individuals are

transferred to a DSH

hospital or JBCT

pre-maturely when

an individual is being

considered for

Diversion.

S.8

Prioritize and/or incentivize

DSH Diversion funding to

support diverting eligible

individuals from the DSH

waitlist.

Policy/

Statutory

Assists in reducing

the DSH waitlist by

prioritizing

individuals on the

waitlist for Diversion

over individuals

likely to be found

incompetent to stand

trial. Individuals

likely to be found

incompetent to stand

trial are also eligible

for DSH Diversion.

The 2021 Budget Act included funding for

existing programs to expand Diversion

programs to divert individuals who have been

found incompetent to stand trial on felony

charges from DSH waitlist. Welfare and

Institutions Code 4136 by trailer bill, SB 129

(Committee on Budget, Statutes of 2021),

also amended to prioritize expansion funding

to individuals found incompetent to stand trial.

S.9

Include justice-involved

individuals with serious mental

illness as priorities in state-

level homelessness housing,

behavioral health, and

community care infrastructure

expansion funding

opportunities

Policy

Supports increased

access to

community-based

treatment for justice-

involved individuals

including felony

ISTs.

While funding and capacity expansion are

longer-term strategies, inclusion in priorities

and planning that is underway now or in the

short-term should occur.

S.10

Augment funding in DSH

Diversion contracts with

counties to provide for interim

housing, including subsidies,

Funding

Addresses concerns

of DSH Diversion

program providers

about insufficient

30

and housing-related costs to

support increased placements

into Diversion.

funding to access

housing for the DSH

Diversion population

S.11

Local planning efforts for

homelessness housing,

behavioral health continuum,

and community care

expansion should include

behavioral health and

criminal-justice partners and

consider providing services for

justice-involved individuals

with Serious Mental Illness to

reduce homelessness and the

cycle of criminalization.

Policy

Supports local

efforts and inclusion

of justice-involved

individuals in

planning and

strategy

development for

local investments

and state-level

grants.

31

Medium-Term Strategies: Solutions that can begin implementation by January 10, 2023

Goals:

a. Continue to provide timely access to treatment.

b. Begin to implement other changes that address broader goals of reducing the number of ISTs.

c. Increase IST treatment alternatives.

#

Strategy

Type

Potential Impact

Other Considerations

32

Statutorily prioritize

community outpatient

treatment and Diversion for

individuals found

incompetent to stand trial on

felony charges for

individuals with less severe

behavioral health needs and

criminogenic risk, and

reserve jail-based

competency and state

hospital treatment for

individuals with the highest

needs. Options include:

• Require

consideration of

Diversion for anyone

found incompetent to

stand trial on felony

charges.

• Treat penal code

1170(h) felonies, for

which the maximum

penalty is a prison

term served in the

county jail rather than

in state prison,

consistent with SB

317 (Chapter 599,

Statutes of 2021)

which requires a

hearing for Diversion

eligibility, if not

Statutory/

Funding

Establishes priority

for Diversion and

community-based

treatment for felony

ISTs whenever

appropriate based

on an individual’s

treatment needs and

criminogenic risk.

Prioritizes utilization

of state-hospital and

jail-based

competency

treatment programs

for those with the

highest needs.

Corresponding operational changes could be

implemented to also develop clinical factors

for determination of treatment in State

hospitals versus jail-based competency

treatment programs. Currently, over referral

to state hospitals and jail-based competency

treatment programs and under-utilization of

Diversion programs and lack of community-

based treatment programs results in lengthy

waitlists and inefficient utilization of inpatient

and jail-based beds.

Implementation of statutory changes may

require funding or other supports related to

court hearings and treatment capacity.

33

Diversion eligible, a

hearing to consider

assisted outpatient

treatment,

conservatorship, or

dismissal of the

charges.

• Change presumption

of appropriate

placement to

outpatient treatment

or Diversion for

felony IST, require

judicial determination

based on clinical

needs or high

community safety

risk for placement at

DSH or in a jail-

based treatment

program, and a

determination that

community resources

are available to meet

the treatment needs

of the individual.

• Reform exclusion

criteria of Diversion

under PC 1001.36 to

“clear and present

risk to public safety”

rather than

criteria of Diversion under PC 1001.36 to

“clear and present risk to public safety”

rather than "unreasonable risk to public

safety."

34

“unreasonable risk to

public safety.”

• Statutorily require the

use of structured

mental health risk

assessments to

assist in identifying

defendants that

should be eligible for

Diversion or

community

treatment.

• Require judicial

consideration of

Diversion at the

outset of criminal

proceedings for

mentally ill

defendants.

• Eliminate the

requirement of a

nexus between the

defendant’s mental

disorder and the

charged offense for

individuals diagnosed

with a serious mental

illness or establishing

a rebuttable

presumption of

nexus.

• Establish a

presumption of

35

Diversion eligibility if

an individual is

determined to be

incompetent to stand

trial and meets

clinical and legal

eligibility, subject to

the availability of a

treatment plan.

Establish a presumption of Diversion

eligibility if an individual

is determined to be

incompetent to stand trial

and meets clinical and legal

eligibility, subject to the

availability of a treatment

plan.

36

M.2

Provide increased

opportunities and dedicated

funding for intensive

community treatment

models for individuals found

IST on felony charges.

Options include:

• Assisted Outpatient

Treatment (AOT)

• Forensic Assertive

Community

Treatment (FACT)

• Full-Service

Partnerships (FSP)

• Regional community-

based treatment and

Diversion programs

for individuals not

tied to any one

county

• Crisis Residential

• Substance abuse

residential treatment

• Psychiatric health

facilities

• Mental Health

Rehabilitation

Centers

• Transitional

residential treatment

Funding/

Policy

Increases access to

community-based

treatment

alternatives for

justice-involved

individuals with

serious mental

illnesses and

reduces the

incarceration.

M.3

Establish a new category of

forensic Assisted Outpatient

Statutory

Increases access to

community-based

treatment

Establishing category would be a medium-

term strategy. However, implementing

programs would be a long-term strategy.

37

Treatment commitment that

includes:

• Housing

• Long-acting

injectable psychiatric

medication

• Involuntary

medication orders,

when necessary, as

ordered by the court,

and appropriate due

process procedures

are followed.

• FACT team

• Intensive case

management

alternatives for

justice-involved

individuals with

serious mental

illnesses and

reduces the

incarceration. A

forensic AOT

commitment would

ensure access to,

and engagement

with an intensive

level of outpatient

services designed to

interrupt the cycle of

criminalization in

lieu of inpatient

restoration

commitment.

M.4

Establishing statewide pool

of court-appointed

evaluators and increase the

number of qualified

evaluators:

• Request counties to

share their lists of

court-appointed

evaluators.

• Identify

demographics and

cultural and linguistic

competence of

evaluators.

Funding/

Operations

Assists courts in

access to expanded

statewide pool of

court-appointed

evaluators and

potentially reduces

the amount of time

individuals wait in

jail for a court-

appointed

evaluation.

Establishing a

diverse pool of court

appointed

38

• Increase court

funding for court

appointed evaluator

pay.

evaluators reduces

the risk that

individuals are

determined to be

incompetent to

stand trial due to

cultural and

linguistic

differences.

M.5

Improve statutory process

leading to finding of

incompetence or restoration

to competence:

• Set time frames for

appointments of

court appointed

evaluators and

receipt of reports.

• Set statewide

standards for court

evaluations and

reports.

• Expand list of

individuals who can

recommend to the

court a need for re-

evaluation if

someone may have

been restored –

noted already

authorized for those

over 60 days.

Statutory

Reduces time in jail

for individuals

awaiting

competency

assessments and

increases quality of

court-appointed

evaluator reports.

Allows an individual

to be reevaluated for

competency after

the initial finding and

before transfer to a

treatment program.

Penal Code 1370 in 2019 was amended to

allow jail providers and public defenders to

request the court to appoint an evaluator to

reevaluate a person’s competency. Welfare

and Institutions Code 4335.2 was added in

2021 to allow DSH evaluators to reevaluate

an individual for competency after they have

been on the waitlist for 60 days.

Implementation of statutory changes may

require funding or other support.

Establishing timeline for court-appointed

evaluators would be dependent upon

increasing the pool of evaluators.

39

M.6

Revise items court-

appointed evaluators must

consider when assessing

competence to include:

• Eligibility for

Diversion

• Likelihood for

restoration

• Medical needs

• Capacity to consent

to medications

• Consideration of

malingering

Statutory

Assists the court in

determining an

individual’s potential

eligibility for

Diversion or whether

another treatment

pathway to

competency

restoration is more

appropriate.

Important to ensure appropriate training,

technical assistance, and quality assurance

measures for court-appointed evaluators are

also implemented in conjunction with this

recommendation, otherwise individuals may

unnecessarily be excluded from Diversion

opportunities.

May also consider whether the court-

appointed evaluator competency assessment

could also include placement

recommendations rather than having a

separate placement performed by the

CONREP Community Program Director.

Would require significant training and

technical assistance on increasing knowledge

of the statewide continuum of placement

options.

M.7

Revise/improve involuntary

medication order statutory

process:

• Involuntary

medication orders

follow the person and

are not specific to the

placement locations.

• Court-appointed

psychologists may

opine on consent

capacity and

potential need for

involuntary

medications when

Statutory

Provides treatment

access and

stabilization for

individuals who do

not have the

capacity to consent

to treatment due to

the current severity

of the symptoms of

their mental illness.

Facilitates improved

care coordination

and rapid re-

stabilization to

prevent

40

providing reports to

the court on

incompetence to

stand trial.

• Remove special

designation

requirements in