Managing

Maryland's Growth

Models and Guidelines

Urban Growth

,.\r.. ,,

Boundaries

The Maryland Economic Growth,

Resource Protection, and Planning Act of 1992

Maryland Office of Planning

This document may not reflect current law

and practice and may be inconsistent

with current regulations.

37

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Prepared Under the Direction Of:

Mary Abrams

James T. Noonan

Principal Staff:

Mike Nortrup

Graphic Design:

Ruth O. Powell

Production & Printing Coordination:

Mark S. Praetorius

The Maryland Office of Planning wishes to thank the directors of county

and municipal planning agencies and their staff; the Cabinet Interagency

Committee and its Technical Support Group; the Economic Growth,

Resource Protection, and Planning Commission; the Subcommittees on

Interjurisdictional Coordination and Planning Techniques; and others

who so graciously gave of their time to review drafts of this publication.

This publication is printed on recycled paper.

38

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

The Maryland Office of Planning

State of Maryland

Parris N. Glendening, Governor

Maryland Office of Planning

Ronald M. Kreitner, Director

August, 1995

MARYLAND Office of Planning

This booklet was written and designed by the Comprehensive Planning

and Design Units of the Maryland Office of Planning as a service to local

governments and planning officials. The author is Mike Nortrup.

Graphic design and production are by Ruth O. Powell and Mark S.

Praetorius.

Additional copies are available from the Maryland Office of Planning, 301

West Preston Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201-2365. Phone: (410) 225-

4562. FAX: (410) 225-4480.

Publication #95-09

1

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD ......................................................................................................... 2

URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARIES IN OTHER STATES .................................................. 4

Oregon ....................................................................................................... 4

Thurston County, Washington ................................................................... 6

Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota ........................................................ 7

Conclusion ................................................................................................. 8

GROWTH BOUNDARIES IN MARYLAND .................................................................. 9

Developing the Boundary ..........................................................................11

Impact Of Boundaries On Local Plans And Ordinances........................... 12

Administering the Growth Boundary ....................................................... 13

Assessing Urban Growth Boundaries in Maryland .................................. 13

METHODOLOGY USED IN CREATING THE URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARY ................. 16

The Basic Steps......................................................................................... 16

Identify Problems and Issues .................................................................... 17

Establish A Public Participation Process................................................... 18

Determine Boundary Goals ...................................................................... 18

Collect Data.............................................................................................. 19

Draw Boundary........................................................................................ 23

Prepare Public Information Program ........................................................ 24

Enact Interjurisdictional Agreements ....................................................... 24

Revise Plans and Ordinances ................................................................... 25

MAKING URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARIES SUCCESSFUL IN MARYLAND .................... 26

THE URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARY AND THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN ..................... 31

BIBLIOGRAPHY .................................................................................................. 33

APPENDIX

Memorandum of Understanding Between Montgomery County and the

Cities of Rockville and Gaithersburg ......................................................... 34

OTHER PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE...................................................................... 37

2

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

FOREWORD

At the core of growth and development issues around the country are

basic questions about where new development is to occur. This issue of

growth is intricately tied to questions of property rights, infrastructure

investment, and environmental protection. Where growth and develop-

ment are issues, such questions are faced by local governments on a

daily basis. Local governments have developed a variety of responses to

them, but a common theme is one of defining suitable areas for growth.

Approaches to defining such growth nodes can range from delineations

of service areas or definitions of adequate public facilities to strictly

defined urban growth boundaries. This publication will examine the use

of growth boundaries as a growth management mechanism.

In Maryland, an increasingly powerful force behind this, and all other

local governments’ efforts to control growth, is the Economic Growth,

Resource Protection, and Planning Act of 1992 (Planning Act). The

Planning Act encodes the Visions as the State’s official growth policy,

which will guide the myriad of development actions in Maryland.

Accordingly, the Planning Act requires that county and municipal plans

be amended so that they include and implement this overall State policy

guide. The first Vision states that “Development is concentrated in

suitable areas.”

A basic premise of the Planning Act is that it is a responsibility of local

governments, through their comprehensive planning processes, to define

those growth areas, whether by growth boundaries or other means.

This booklet is one of a series of Models and Guidelines published by the

Maryland Office of Planning to help local jurisdictions meet the chal-

lenges and opportunities presented by the Planning Act. This booklet

will outline the use of urban growth boundaries in Maryland and else-

where. It also will detail those actions that must be taken to make

growth boundaries successful.

An urban growth boundary is a line on a map used to mark the separa-

tion of rural land from land on which growth should be concentrated.

The concept can be traced at least as far back as the 16th Century when

England’s Queen Elizabeth I decreed that no building could be con-

structed within three miles of London’s city gates. This decree thus

created a greenbelt between the City walls and new development.

In recent years, American planners have also used this centuries-old

method of growth control. One intent, as in Elizabethan England, is to

protect open space lands. Another perhaps more pressing goal is to

reduce and contain urban sprawl. Because such boundaries frequently

3

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

represent a coordinated, interjurisdictional effort to determine where

urban development can, and cannot go, they can serve as a valuable

growth management tool.

For the purposes of this booklet an urban growth boundary is a line that

is a specific and integral element of a comprehensive plan. Regardless of

the method used to define the boundary, it differs from other techniques

to define appropriate areas for growth because it is proactive. An urban

growth boundary provides guidance to decision-makers regarding the

location of urban services and infrastructure. In its strongest form it can

be changed only through a formal amendment to a comprehensive plan.

Such lines cannot be moved as the result of incremental changes to

infrastructure service areas or boundaries.

“Urban Growth Boundaries” begins by examining how boundaries are

used elsewhere in the United States. The booklet then focuses on the

Maryland jurisdictions that use them. It contains an analysis of their

strengths and weaknesses and how urban growth boundaries can be

created and improved. To obtain information on boundaries in Mary-

land, the authors interviewed planners and other professional staff from

Baltimore, Frederick, Howard, Montgomery and Washington counties.

Planners from the cities of Frederick, Gaithersburg, Hagerstown and

Rockville were also consulted. Comprehensive plans and other relevant

documents from these jurisdictions also were examined as part of this

study.

This booklet is organized in five parts.

• Part I examines the uses and successes of urban growth bound-

aries around the United States.

• Part II examines the rationale for establishing growth boundaries

in Maryland. It discusses the methodology and criteria used to

determine boundary locations. It then explains how new deve-

lopment within boundaries is administered and examines the

success of boundaries in achieving their growth management

goals.

• Part III contains a checklist of suggested items to consider when

planning for, and drawing the urban growth boundary.

• Part IV provides guidance for actions to take and mechanisms to

use, if boundaries are to be successful in managing growth.

• Part V explains how urban growth boundary language can be

integrated into the comprehensive plan.

4

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARIES IN

OTHER STATES

Oregon

It appears that the first application of the urban growth boundary con-

cept in the United States was in Lexington, Kentucky during the 1950’s.

The idea gradually spread. By late 1992, growth boundaries were a part

of statewide enabling legislation in six states. They also were used in a

number of cities and counties across this country.

Some jurisdictions in these other states have far more complex and

ambitious urban growth boundary programs than those in Maryland.

As in Maryland, the boundaries in those states enclose urban growth

areas which include both incorporated and unincorporated land. They

designate where urban growth exists or is planned, and areas where it is

discouraged.

Boundaries in these other states are established to accommodate growth

over a particular period, generally 20 years. Accordingly, in developing

boundaries, these jurisdictions make detailed calculations of land de-

mands for the appropriate period. These states generally require peri-

odic evaluations of their growth boundaries and adjustments to the lines

as necessary.

Because the scope is generally interjurisdictional, a cooperative regional

approach is used to make such boundaries successful.

Oregon’s 1973 Land Conservation and Development Act required all

incorporated cities to designate growth boundaries. All have done so.

The Portland urban growth boundary, established in the late 1970’s,

encompasses numerous cities as well as unincorporated land. The cities

adopt their own comprehensive plans. The counties’ comprehensive

plans cover the unincorporated land lying within the growth boundaries.

Much of the day-to-day management within each boundary is conducted

by the Metropolitan Service District, the nation’s only elected regional

government. The District approves the extension of public facilities and

provides guidelines for adjusting the Portland boundary. The District

also exerts some control over local zoning. For example, the District

requires that city zoning allow as many as 10 units per acre on lands that

will accommodate multifamily residential development.

The major purposes of Oregon’s urban growth boundary program are to

prevent sprawl and to protect agriculture and forestry: two of that state’s

leading economic sectors. An August, 1990 evaluation of Oregon’s

boundary program revealed that it had achieved some success. Rampant

5

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

sprawl outside the boundaries of the Portland metro area, for example,

had been drastically reduced.

The study, focussing on land development between 1985 and 1989, found

that in the Portland metropolitan area, only 9.0 percent of the single-family

units, 0.5 percent of the multiple-family units and 1.2 percent of the new

subdivision lots were outside the Portland urban growth boundary. No

significant commercial or industrial development occurred outside.

However, the study of the Portland metro area urban growth boundary

showed that 85 percent of residential subdivision lots that were approved

outside of the boundary lay immediately adjacent to that line. This pre-

dominately low-density development would act as an impediment to

moving the urban growth boundary outward. It also acts as a block to

the successful future urbanization of these areas. There remains a great

demand for such low-density residential development. There is diffi-

culty in economically serving this large-lot development with infrastructure.

Also, opposition to higher-density development inside the boundary has

intensified. Barriers have developed to moving the line outward because

strong interest groups, composed of local residents, oppose the line’s exten-

sion.

While sprawl was slowed outside the boundary, it continued inside.

Residential development within the Portland boundary between 1985

and 1989 was below allowable density. Single-family residential develop-

ment in the Portland metropolitan area occurred at only 68 percent of

allowable density. In the “urbanizable” portion of the boundary (defined

in the local plan as land available and suitable for development once

urban services are provided), single-family development densities were

only 59 percent of that allowed. Multifamily development was at 73 percent

of density allowed. To many observers, these “below-target” densities are

also sprawl. Still, the development has occurred in an area slated for

growth.

Infrastructure issues also exist. Vacant land in outlying areas within the

boundary is easy to develop. However, it is hard to serve with infrastruc-

ture because costly urban services cannot keep up with the demand. Older

urban areas, on the other hand, are easier to serve because the infrastruc-

ture is already in place. However, redevelopment is generally harder

than new construction because of difficulties in assembling adequate

land and higher land prices in more urbanized areas. There also are

practical difficulties in construction when the surrounding properties are

built up. Local opposition also can be an impediment to effective

redevelopment.

6

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

The Portland urban growth boundary is considered a qualified success.

As previously stated, it has drastically reduced sprawl in rural areas

beyond it. Because growth is strongly encouraged within the bound-

aries, the approvals of developments there are predictable. This predict-

ability shortens approval time and saves money for developers and

homebuyers. The Portland urban growth boundary has widespread

support because it has made growth more orderly and predictable.

Even though much growth is confined within the boundary, housing prices

there have not risen dramatically as some predicted would occur. Part of

the relatively low price rise results from the availability of major infrastruc-

ture for new development. Additionally, Oregon State has streamlined

development reviews, making them more predictable and less time-con-

suming. A final contributing factor in the lack of a rapid price rise lies in the

fact that there is vacant land available for new development plus ample infill

and redevelopment opportunity within the growth boundary.

In the early 1980’s, the Thurston Regional Planning Council, a County

regional planning agency, developed an agreement among the County

and three of its municipalities to establish an urban service area bound-

ary. The purpose of the boundary was to concentrate urban develop-

ment within planned growth areas, provide high-quality basic services at

lowest cost, and encourage orderly growth consistent with rational

provision of public services. The line would establish the outer limit of

urban development, annexation and urban service extension.

A 1986 evaluation showed that a majority (60 percent) of new housing

units were being built outside the three cities. Development within the

boundary was occurring below desired densities, often in a sprawl

pattern. In 1988, the four jurisdictions responded by creating a two-

tiered boundary featuring short-and long-term growth areas and

adopted an Urban Management Agreement to govern the responsibilities

of each jurisdiction. To slow sprawl, they attempted to stage the exten-

sion of utilities gradually outward from the urbanized core. The short-

term service area provides for growth over a ten-year period. The

long-term area is slated for urban growth and services over an 11 to 25

year period.

Their voluntary agreement outlines a common approach to growth and

the provision of public services and facilities. It also establishes stan-

dards to guide each jurisdiction’s land use planning decisions in a way

Thurston County,

Washington

7

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

that will achieve common growth management goals while leaving the

power with each jurisdiction to control its own land use. The agreement

allows minimal extensions of municipal services beyond the short-term

growth area. It also has established a joint land use planning process to

implement the boundary. The jurisdictions jointly agree on zoning,

densities and land uses in both the short-term and long-term areas. Some

cities adopted a policy of reimbursing the County when annexing land

on which the County had made a substantial capital improvements invest-

ment.

While extensive data are not yet available, it appears the boundary

program is a success. There have been few requests for subdivision

approvals in rural areas. Thurston County has supported the boundary

program by downzoning land outside the long-term boundary for very

low densities. Few utility extensions have gone beyond the short-term

growth area portion of the boundary, and none beyond the long-term

line.

This arrangement also is positive in terms of the intergovernmental

cooperation that has occurred through strictly voluntary agreements.

The previously-cited city/County land use and revenue sharing agree-

ments are examples. In addition, the current agreement calls for mutual

concurrence among the County and cities before revising the boundaries

of the urban growth area.

The Metropolitan Land Planning Act of 1976 gave the Metropolitan

Council limited planning authority over the Minneapolis/St. Paul metro

area, a seven-county region covering 3,000 square miles and home to two

million residents.

The Council uses plans for water and sewerage and other services to

control the location of development. Jurisdictions in the metro area are

required to prepare comprehensive plans that are consistent with the

Council’s regional plans for highways, transit, water and sewerage,

housing, solid waste management and health. Council authority, how-

ever, extends only to those areas considered of regional significance.

The Council and area jurisdictions also developed the Metropolitan

Urban Service Area (MUSA), where development would be encouraged

in some areas and discouraged in others. Urban expansion in each city is

negotiated with the Council in accordance with the regional comprehen-

sive plan. Service extensions are granted by the Council on a city-by-city

Minneapolis and

St. Paul,

Minnesota

8

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

basis, based on needs.

The MUSA and its associated policies have affected the pattern of develop-

ment in the region. New development in the rural areas of the MUSA has

declined dramatically since 1978, two years before the growth plan was

implemented. The areas where urban services are provided have expanded

in a manner consistent with guided growth. Major regional highways and

sewerage facilities have expanded only within the urban area. Neighboring

jurisdictions within the region are kept aware of each other’s plans to a

much higher degree than before the Act’s passage. Finally, the importance

and primacy of planning on a regional basis have been established.

There have been many, mostly minor, adjustments to the MUSA bound-

ary line over the years. Some cities have petitioned the Council for major

expansions into rural areas and rezoning requests are expected to follow.

These cities and counties had differing issues and problems that their

respective urban growth boundaries were intended to address. Like

Maryland, they experienced successes and failures. These jurisdictions

have generally achieved their goal of limiting sprawl beyond their

boundaries. However, low-density development and the bypassing of

developable land parcels nevertheless occurred inside boundaries. There

was also some pressure to extend development into rural areas.

Minnesota, Oregon and Washington also used the powers of regionalism

to plan their growth boundaries and encourage their success. In Minne-

sota and Oregon, regional authorities have at least some statutory pow-

ers to provide overall direction, planning and coordination. In

Washington’s Thurston County, this regionalism is achieved through

voluntary agreement. Regardless of the arrangement, the local jurisdic-

tions in these states must plan and provide services within a coordinated

and established regional framework. Local plans must be consistent with

regional goals and policies.

While each state implements its urban growth boundary program in a

different fashion, regional cooperation is a common element in all such

programs. For an urban growth boundary to successfully control growth,

it is imperative that the participating towns and counties develop coop-

erative planning, zoning, infrastructure and other mechanisms to stage

and guide development. While Maryland does not have the formally-

established regional organizations that are the conduit for interjurisdic-

tional cooperation in States such as Minnesota and Oregon, our need for

such cooperation is no less acute.

It is therefore important to examine how this all-important ingredient is

integrated into Maryland jurisdictions’ growth boundary programs and

Conclusion

9

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

GROWTH BOUNDARIES IN MARYLAND

The 1950’s saw the beginning of a population explosion in Maryland that

would more than double its population from 2,343,001 in 1950 to over

five million in 1994.

Much of this population growth resulted in large-lot residential sprawl

and supporting commercial development spreading out from the older

built-up population centers into the countryside. This new development

pattern consumed agricultural and environmentally-sensitive lands. The

pattern also resulted in a loss of community character in what had

formerly been rural settlements. Often it quickly overburdened the rural

road network, schools and other public services that local jurisdictions

had provided for these areas, forcing inefficient extensions of urban

facilities.

Accelerating growth also increased development pressures on vacant

land adjacent to municipalities. This led to ever-increasing municipal

efforts to annex prime development parcels. Municipal expansions,

however, often created conflicts with counties that envisioned different

uses for the land.

These growth-associated problems forced jurisdictions in Maryland to

adopt a variety of planning tools and other measures to control develop-

ment. Urban growth boundaries were one of the measures chosen to

encourage growth in selected areas. In the late 1960’s, Baltimore County

became the first Maryland jurisdiction to adopt such a boundary. Others

followed over the next decade.

The form of growth boundary used depends on the type of problem or

circumstance it is to address. In some instances, the boundary is simply

an annexation limit line that represents agreement between town and

county on what lands should ultimately be included in the municipality.

The development anticipated on these parcels is most likely to be the

more urban types of density/intensity that normally occur within mu-

nicipal limits. Frederick City and Frederick County, along with

Gaithersburg and Montgomery County, have such annexation limit lines.

Properties are included within those lines because they are adjacent to

the municipalities or because their annexation would eliminate irregulari-

ties in municipal boundaries. These properties also could be readily

served by municipal water, sewerage and other infrastructure.

A more complex solution is required where sprawl development reaches

far beyond municipal environs into the countryside. This type of pattern

creates more widespread problems. It consumes extensive amounts of

land. It overtaxes services or forces expensive and inefficient infrastruc-

10

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

ture extensions from either the town or county. It also endangers agricul-

tural land and sensitive environmental features.

Growth boundary lines created under these circumstances are intended

to do far more than simply designate parcels that should ultimately be

annexed. This type of boundary delineates a larger area, often at least

partially unincorporated, in which the county hopes to contain and

attract dense or intense development. This type of boundary is generally

created with the understanding that only very limited lower density

development may occur beyond its limits.

More so than with simple municipal annexation limits lines, this type of

urban growth boundary signifies a countywide effort to contain growth

near towns or built-up areas. These more extensive growth boundaries

appear in Baltimore, Frederick, Howard, Washington and Montgomery

counties. They demand close coordination between municipal and

county governments.

Baltimore County’s urban growth boundary, known as the Urban-Rural

Demarcation Line (URDL), includes all of the County’s urbanized land

around the City of Baltimore. The URDL also extends into some unde-

veloped areas where future growth is proposed. The primarily-

agricultural and rural northern portion of the County is beyond the

URDL. The URDL was put in place to protect these areas from develop-

ment.

Frederick County has several boundaries. The largest area includes the

City of Frederick, the area governed by its annexation limits line and

nearby unincorporated land. Boundaries have also been adopted for

Thurmont and Mount Airy, and for unincorporated growth areas such as

Point of Rocks.

Howard County’s Suburban-Rural Demarcation Line encloses its more-

developed eastern part, including Columbia and Ellicott City.

Washington County has adopted a generalized urban growth boundary

line covering its north central area, including Hagerstown, Funkstown

and Williamsport. Smaller boundaries encompass Boonsboro and

Smithsburg.

11

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Local governments in Maryland have established urban growth bound-

aries for a variety of reasons:

• To control residential sprawl.

• To provide a tool to defend against inappropriate rezonings in

rural areas.

• To create rational municipal annexation limits.

• To control utility extensions into rural areas.

• To protect agricultural land.

• To concentrate growth in selected places.

• To let property owners know whether their land lies in a develop-

ment or potential development area.

• To effect coordination between town and county concerning road

paving and right-of-way widths, as well as locations of future

transportation facilities.

• To augment the comprehensive plan as a tool for controlling

development.

Urban growth boundaries in Maryland generally are not as sophisticated,

or scientifically derived, as those in other states. Counties and munici-

palities around the United States often have used sophisticated proce-

dures to determine exactly how much acreage to include within their

growth boundary lines and exactly where the boundaries are drawn.

These methods include detailed population and housing unit projections

that are used to determine how much land would be needed in the

future. Density targets often are established within the growth bound-

aries so that projected development will occur at high enough densities

to be accommodated on the available acreage.

No Maryland jurisdiction has calculated an “optimal” land area within its

urban growth boundary based solely on land demands created by pro-

jected future growth, nor assigned an overall density target. Howard

county simply used its 20-year sewerage service area to establish its

boundary. Baltimore County did much the same, while ensuring its

Developing the

Boundary

12

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Urban-Rural Demarcation Line encompassed all built-up areas.

Frederick County’s growth area boundary encompassing Frederick City,

Walkersville, and portions of the surrounding County, is based partially

on projections of population and dwelling units and resulting land

demand calculations. In addition however, water and sewerage service

area considerations also play a strong part. Washington County consid-

ered a variety of factors, including existing water and sewerage service

areas, soils, farm ownership patterns, population holding capacity based

on existing zoning and projected population. Nevertheless, the resulting

boundary will accommodate far more population than is projected to

settle there in the foreseeable future.

In Maryland, local governments used no special procedures or laws to

officially adopt their growth boundaries. The boundaries were included

as part of comprehensive plans and were adopted under the usual plan-

adoption procedures.

While all boundaries are shown on the comprehensive plan maps for

each jurisdiction which uses them, the amount and degree of reference to

them in comprehensive plan texts varies widely. Most plans do not

devote significant discussion to the importance of the boundaries in

terms of growth management or their effects on specific areas of plan-

ning and development policy. Howard County does reference its growth

boundary throughout its comprehensive plan.

Most local zoning and subdivision regulations have not been amended

specifically to reflect growth boundaries. Baltimore County uses the

Urban Rural Demarcation Line in its Chesapeake Bay Critical Areas

program. Zoning provides the greatest amount of protection to those

Critical Area lands lying outside the URDL.

The general policy in these jurisdictions is to separate the higher-density

urban and suburban uses from the lower-density ones in rural areas.

Zoning does not always support this goal. Howard and Washington

counties, which lack agricultural zones that substantially limit develop-

ment potential, are cases in point. The lack of zoning that effectively

restricts growth in rural areas can result in a great deal of sprawl residen-

tial development beyond local boundaries. Howard County strove to

focus development through its 1972 comprehensive plan’s reduction in

the 20-year planned water/sewer service area. The County also used its

1993 Comprehensive Zoning Plan to eliminate all rural, low-density zoning

within the planned water/sewer area and substitute higher-density

Impact Of

Boundaries On

Local Plans And

Ordinances

13

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

residential or mixed-use classifications in its place.

Unlike local governments in some other states, Maryland jurisdictions

have not established special agencies, bodies or organizations to adminis-

ter development and growth within the boundaries. The evaluation,

approval and monitoring of private development projects remain in the

hands of the local government. Development reviews are generally

treated in the same fashion inside and outside of the growth boundary.

Few streamlining or other measures to alter development reviews for

projects within urban growth boundaries have been implemented to

encourage more development there.

In cases where both incorporated and unincorporated lands lie within the

growth boundaries, no formal multi-jurisdictional bodies have been

established to administer the development review process. However, in

most cases there is frequent staff interaction, notification and informa-

tion-sharing between cities and counties whose land lies within urban

growth boundaries. In Frederick, Montgomery and Washington coun-

ties, municipal and county agencies exchange information on proposed

subdivision plats and site plans, rezoning, variances and special excep-

tions and other actions. Agendas for upcoming planning commission,

board of appeals and similar meetings also are shared.

Frederick County supports Frederick City’s annexation limits line by

referring potential developers of those parcels lying within that bound-

ary, to the City. In this way, developers also receive information indicat-

ing that the subject property(ies) will ultimately be annexed. Builders are

then able to plan their projects in accordance with City ordinances and

other development guidelines which will govern them.

The only formal written urban growth boundary agreement is a Memo-

randum of Understanding (MOU) among Montgomery County,

Gaithersburg and Rockville. This is essentially a general policy docu-

ment, in which each signatory agrees to respect the interests of the others

in broad areas of concern when making decisions concerning develop-

ment within its own boundaries. The MOU appears at the end of this

pamphlet.

The counties using growth boundaries generally express satisfaction with

the effectiveness of this tool in controlling growth. The lines have a

major perceived advantage in their specificity. Local governments

believe this clarity gives boundary lines major growth management

Administering

the Growth

Boundary

Assessing Urban

Growth

Boundaries in

Maryland

14

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

advantages over the more traditional and generalized comprehensive

plan-identified growth areas. A boundary line:

• Clearly shows where growth should and should not go. This is a

very important factor in Baltimore County where community

groups are very much aware of the location of the Urban Rural

Demarcation Line. There is a very strong local tradition of oppos-

ing proposed rezonings, extensions of public facilities or any

other actions that would compromise the URDL’s integrity.

• Provides specific limits beyond which water/sewerage, major

thoroughfares and other public infrastructure should not be

extended.

• Lets property owners know if their land will be developed at an

urban, or rural use and density.

• Sets the limits of urban expansion, therefore giving a sense of

permanence to agricultural areas. This encourages landowners to

sell easements and enter agricultural districts.

• In the case of an annexation limits line, lets a property owner

know which jurisdiction will ultimately make development

decisions.

Boundary lines also help in some county efforts to revitalize older urban

areas and encourage infill development on vacant parcels. This is be-

cause development beyond the urban growth boundary line is restricted.

Developers must look harder for opportunities within the boundary.

Thus, marginal properties or older urban areas receive closer scrutiny as

development or redevelopment candidates than would be the case if

more land were available beyond the line.

The effectiveness of urban growth boundaries in Maryland is also questioned:

• Because there are no optimal density goals established for urban

growth boundary areas in Maryland, excess land beyond the

needs of growth is always included. This ready availability of

land presents many site options to potential developers. Within a

boundary it also results in sprawl development or disjointed

infrastructure extensions.

• Some counties with growth boundaries do not have a restrictive

agricultural or conservation zone. Zoning then presents no

disincentive to develop in rural areas, because there is no clear

15

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

difference between permissible densities on either side of the

boundary.

• There also are problems when the urban growth boundary line

includes both municipal and county land. In these instances,

each jurisdiction involved often expressed the belief that the other

acted alone, without considering its interests or advice. While

each jurisdiction acknowledged that it was given an opportunity

to comment on proposed developments elsewhere, each

nevertheless expressed the belief that the other would do what it

wanted, regardless of its neighbor’s concerns.

16

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

METHODOLOGY USED IN CREATING

THE URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARY

The Basic Steps

A variety of growth-related issues and problems confront State and local

government in Maryland. Any one of these issues could prompt a

jurisdiction to enact urban growth boundaries.

Perhaps all that is needed is for a town and county to agree on a line

showing that town’s maximum annexation limits. However, more

complex issues created by sprawl development often require more

complex interjurisdictional solutions. A line created under these condi-

tions may delineate an area that includes both municipal land, nearby

properties that are considered likely annexation prospects, and other

acreage that is not a prime target for annexation but is still appropriate

for development. Because development on those parcels affects a city or

town even though that land won’t be annexed, the municipality desires

agreement with the county on a development pattern agreeable to both

jurisdictions.

Within the urban growth boundary line, various densities of residential,

commercial and industrial development appear. The more dense urban

styles generally predominate. This development would be governed

under a number of specific rules and regulations.

The reasons for creating the boundary, the density and use goals set for

it, greatly affect the methodology that will be used to bring it to pass.

This is true even though the common goal of all such growth boundaries

is to identify growth and non-growth areas.

This section presents a comprehensive listing of the types of information

that should be collected and analyzed when preparing to enact an urban

growth boundary. It is intended as a guide only. A jurisdiction may

conduct as much of this research as it deems necessary, depending on the

complexity of the problems it seeks to address.

Regardless of the level of detail to be pursued, all local governments

planning an urban growth boundary should follow certain basic steps:

• Identify problems and issues the boundary line must address.

• Establish a public participation process to generate support for

the boundary.

• Determine specific goals for the boundary and its role in the

jurisdiction’s growth management efforts.

17

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Identify Problems

and Issues

• Gather and analyze data needed to determine the location of the

boundary and the amount of acreage to be included within it.

• Draw the boundary.

• Prepare an appropriate public information program.

• Enact necessary interjurisdictional agreements.

• Amend the comprehensive plan, ordinances, and other imple-

mentation tools to reflect the urban growth boundary.

Before deciding on the type of urban growth boundary line it needs, the

jurisdiction must first identify the development-related problems that the

line would address. The following are typical:

• Difficulty reaching a city/county consensus concerning where,

and in what direction, a municipality should grow.

• A development pattern that threatens agricultural land and other

rural resources.

• Growth that overburdens public services.

• Development that forces illogical or inefficient extensions of

public services.

• Prohibitively high taxes for infrastructure construction or mainte-

nance, now or for future, if existing development trends continue.

• Development leaving unused service capacities in some areas

while overburdening those elsewhere.

• Leapfrog, or sprawl development that bypasses significant

amounts of developable land.

• Abandoned and deteriorating older urban areas as development

moves outward.

18

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Establish A

Public

Participation

Process

Public participation is an important aspect of a comprehensive planning

process. If the plan is not prepared with a process that builds consensus,

the chances for approval or successful implementation are damaged.

The urban growth boundary will be the most visible and understandable

part of a comprehensive plan. A line having a direct impact on the

character of an area should be drawn with the active participation of

community members who will view themselves as either “winners” or

“losers” when the line is approved.

A process for actively soliciting public participation and input should be

a part of each of the remaining steps. It is especially important in two

areas. First, in establishing goals, which will be part of any “visioning”

efforts in the comprehensive planning process. Second, in drawing the

line, which will build public support and help to identify any additional

issues on the border of the growth area.

After identifying issues and the problems of growth, the jurisdiction

must determine how an urban growth boundary would help. The

following are specific goals that could apply to a jurisdiction’s growth

boundary:

• Promote compact development.

• Provide efficient, cost-effective infrastructure.

• Preserve natural resource lands and open space, including farm-

land.

• Prevent traffic congestion on rural roads.

• Retain identifiable edges of towns and maintain community

character.

• Prevent sprawl by defining urban growth areas.

• Prohibit development that requires or encourages urbanization of

lands that are unsuitable.

• Contain urban development in planned urban areas where basic

services, such as water/sewerage, schools, police and fire protec-

tion can be efficiently and economically provided.

Determine

Boundary Goals

19

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

• Ensure the economical use of tax dollars in locating infrastructure

and providing services for the benefit of all citizens within the

urban growth area.

• Avoid tax increases for the purpose of financing duplicative or

other inefficient infrastructure expansions.

• Provide property owners greater security in long-range planning

and investments by delineating exactly where urban growth can,

and cannot go.

• Protect the integrity and economic viability of central cities and

other urbanized commercial areas.

• Promote rational funding of utility extensions, transportation

facilities and schools, to match planned growth.

Before the urban growth boundary line can be drawn, the jurisdiction

must thoroughly examine available information about the status of land

use and development, infrastructure availability and regulatory consider-

ations. This knowledge of existing conditions is needed to devise an

adequate boundary and supporting programs.

A comprehensive data-collection effort is necessary for the geographic

area that the boundary is likely to contain. Early public input is critical.

The following is a list of information topics to consider:

• Examination of services (such as water/sewerage, schools, police

and fire protection) provided to the affected area

- facility locations

- service areas of each facility

- levels and capacities of services provided

- plans for expansion or extension

- adequacy of each service, present and future

- condition of each facility

Collect Data

20

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

- costs of service provision.

• Demographic data

- current and projected population

- existing housing units by type

- projected housing needs by type based on existing

trends and development scenarios

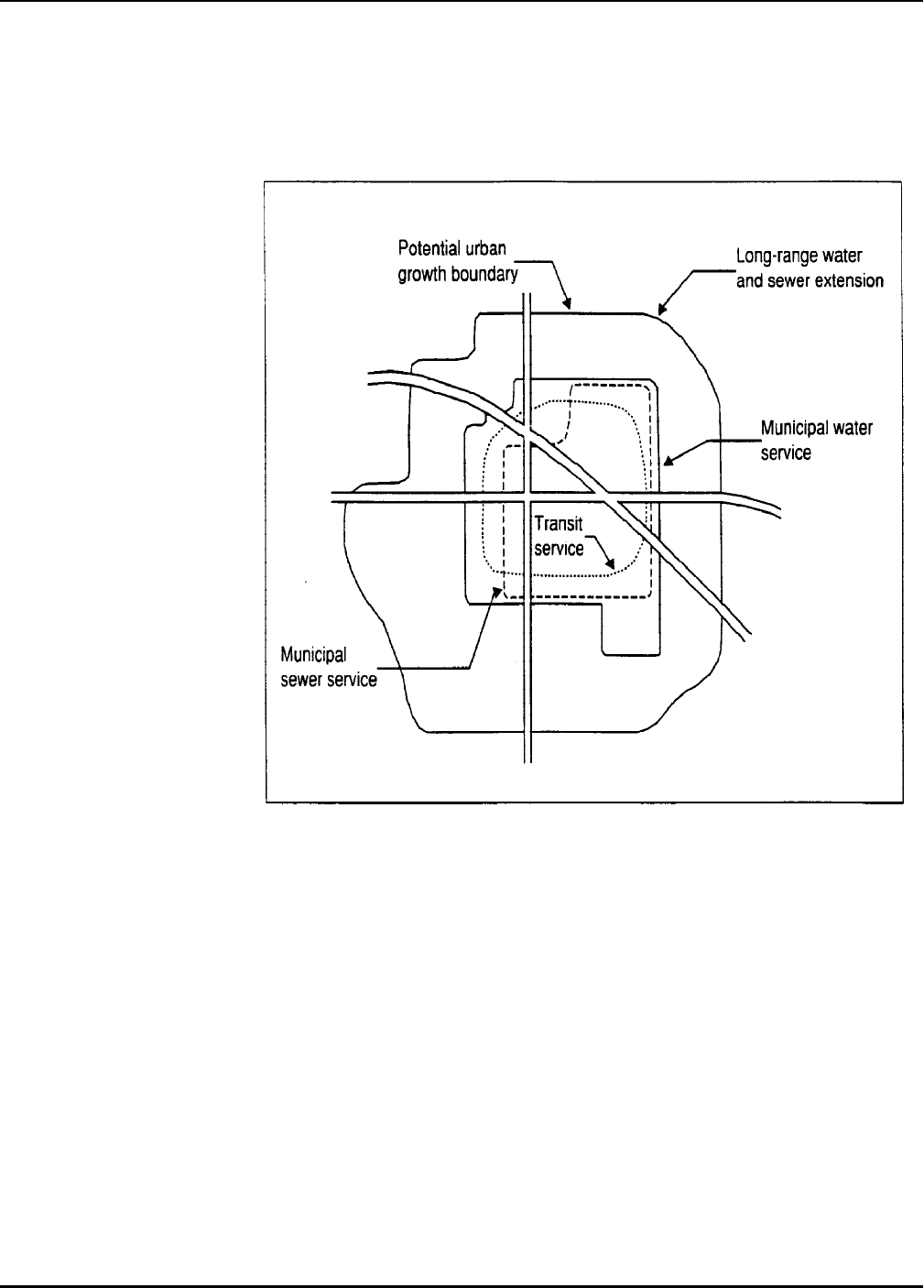

The growth boundaries can be derived by comparing the various maps

of service areas and taking into account the desired level of service and

available funding.

Reprinted with permission of the American Planning Association. From PAS Report

#440 Staying Inside the Lines: Urban Growth Boundaries (November, 1992)

21

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

- economic and commercial development projections

• Land use data

- existing land uses, residential densities and nonresidential

intensities

- approved, but unbuilt or incomplete, developments, with

proposed densities and intensities.

• natural feature data and mapping, with emphasis on conditions

that limit or prohibit development:

- floodplains

- steep slopes

- endangered species habitats

- watersheds, particularly areas to be left undeveloped or

developed under constrained circumstances

- water bodies, including streams and their buffers

- prime agricultural land

- geologic features

- aquifer recharge areas

- well fields

- drainage basins

- wetlands

- forest lands

- other natural areas

22

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

- historic sites

• Local policies related to land use and development, including

recommendations of comprehensive plans and other documents

concerning:

- annexation

- proposed housing types and densities

- redevelopment and infill

- intergovernmental coordination.

• Effects of local regulations and actions influencing the boundary

and development within

- existing zoning patterns within proposed boundary

- effects of development pattern on uses, along with density

and intensity of development

- resulting holding capacity of vacant land

- anticipated or proposed rezonings

- relevant stipulations of subdivision and other ordinances,

such as those governing dissimilar uses on adjacent lands,

which affect the density, intensity and siting of development

within the boundary

- agricultural land preservation

- existing and proposed resource protection programs such as

flood control and standards for watershed protection

- growth-control measures such as adequate public facilities

ordinances

• Market conditions affecting the sale of residential, commercial

and industrial property.

• Densities established by local jurisdiction actions and develop-

23

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Draw Boundary

ment trends

- overall residential density goal set for the land lying within

the boundary.

- existing density ranges and caps as established by local zoning.

- density achieved under existing development pattern.

• Existing density vis-a-vis infrastructure capacities.

Once this information has been collected and properly analyzed it be-

comes the basis for drawing the actual boundary. Of significant impor-

tance is the fact that this data gives the jurisdiction the ability to

determine how much land will be needed within that line.

The boundary must encompass the existing urban area, plus the amount

of acreage that will be needed to accommodate projected land require-

ments within that general growth area. Additional acreage may be

needed to allow an array of alternate development sites sufficient to meet

market needs. The following factors must be considered in determining

the optimal size of the area to be included in the boundary:

• Projected population, commercial and industrial growth.

• Years of growth the boundary is expected to accommodate.

Oregon, for example, scales its boundaries to accommodate 20

years projected population growth.

• Overall target density proposed for the land within the boundary.

• Amount of land needed to accommodate growth and supporting

infrastructure given target density.

• Density limits established by existing zoning and density

achieved under the existing development pattern.

• Proposed density vis-a-vis infrastructure capacities.

Once these factors have been properly analyzed, the line itself is drawn.

While some acreage covered by environmentally-sensitive areas and

appropriate protective buffers will undoubtedly fall within the boundary,

this land must not be considered as part of that acreage needed to sup-

24

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Prepare Public

Information

Program

port anticipated development.

The entire developable area within the boundary and planned for devel-

opment could be made available for immediate use. An alternate ap-

proach is to implement a phased development schedule within the

boundary. One part would be available for immediate use, or develop-

ment within a certain short-term time frame. The other portion can be

held in reserve for development over the long term.

The local jurisdiction should educate the public concerning the need for

the urban growth boundary and its central role in the control of develop-

ment. Comparison of infrastructure and other public costs under the

existing development trend to those anticipated under the more con-

trolled and compact development pattern created within the proposed

boundary, provides a strong argument to support this action. It also is

important to advise the public that there will be a clear method of deter-

mining whether an individual property lies within, or beyond the line.

All governments whose land falls within the urban growth boundary

should concur on the problems the boundary is to address, and sign an

agreement specifying their respective roles in addressing them. Jurisdic-

tions with special districts that provide services within the boundary

should also sign the agreement. This agreement should cover the means

by which the signatories will interact in developing and revising the

boundary. It should also clearly explain how the signatories will cooper-

ate in coordinating planning, development approvals, provision of

infrastructure and other public services and other measures to ensure the

boundary’s success as a growth management measure. The agreement

should specifically include requirements for interjurisdictional circulation

of information concerning proposed development, as well as meeting

agenda, and draft amendments to comprehensive plans, zoning, and

Enact

Interjurisdictional

Agreements

25

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Revise Plans

and Ordinances

other development ordinances.

Once the urban growth boundary is enacted, each participating jurisdic-

tion must make necessary amendments to its comprehensive plan. It

must also carefully examine its zoning ordinance and other implementa-

tion mechanisms to determine where amendments are required. For

example, the zoning map and/or text may have to be revised if the

amount of zoned land within the growth boundary is insufficient to meet

holding capacity and density goals established for that area. Revisions

may be needed in water/sewerage, school or roads plans if the capacities

of these services aren’t sufficient to meet population and density/inten-

sity targets as established by the proposed urban growth boundary.

26

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

MAKING URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARIES

SUCCESSFUL IN MARYLAND

The Jurisdiction Should

Gain Public Support for

the Line

In many areas of the country, urban growth boundaries have proven

useful in controlling development. By placing a well- defined line on a

map, a jurisdiction clearly states where it wishes growth to occur.

A boundary line that adequately controls growth must be supported in a

myriad of ways. This section identifies and discusses the characteristics

a successful urban growth boundary must have, and the actions a juris-

diction must undertake to successfully meet the line’s growth manage-

ment goals.

The jurisdiction must gain public support for the line by demonstrating

the need for it. Having the public as “watchdog” will keep pressure on

local appointed and elected officials to preserve the integrity of the line.

If a growth boundary takes in too little land to accommodate the ex-

pected increases in population, there will be pressure for that growth to

skip beyond the boundary into areas intended for rural use. On the

other hand, a boundary drawn too large invites inefficient, sprawl devel-

opment, with accompanying negative infrastructure and environmental

impacts. To be effective, the boundary should encompass an amount of

land equal to the projected population increase by a certain date, plus an

additional amount of acreage to allow an acceptable range of individual

choices. In other states, this latter figure usually amounts to an addi-

tional 20-25 percent beyond the amount of land physically needed to

accommodate projected growth.

To determine land consumption, the jurisdiction must establish an

overall target residential density for the land lying within its growth

boundary. Residential zoning categories within the growth area should

vary sufficiently to promote an appropriate mix of housing types. How-

ever, the jurisdiction should ensure that the overall density within this

growth area is sufficient to support the economical placement of infra-

structure, the provision of services and the efficient use of land.

As that line on the map which divides areas of growth and non-growth,

the urban growth boundary may be the jurisdiction’s strongest and

clearest single growth management statement. For this reason, it must

occupy a central place in the comprehensive plan’s blueprint for future

development.

The Line Should

Encompass a Realistic

Amount of Land

Needed to

Accommodate

Anticipated Growth

The Line Should be

an Integral Part of the

Comprehensive Plan

27

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

The goals and objectives of the plan should articulate the need for the

boundary and outline its pivotal role in influencing growth management

decisions. The individual transportation and community facilities sec-

tions of the plan should guide the provision of these facilities vis-a-vis

growth and non-growth areas as established by the boundary. The plan

should identify how and where to avoid infrastructure investments that

lead to unwanted development. The sensitive areas element should

explain how environmental features will be protected within and beyond

the development areas.

To ensure that the boundary will continue to reflect growth management

needs over time, the plan also should require a periodic evaluation of the

boundary to determine if it should be adjusted. However, adjustment

should come only after proper analyses are conducted. Any adjustment

should be reflected in, and be implemented by, an amendment to the

plan itself.

As the basis for the jurisdiction’s growth management programs, the

plan should specify the target density for the growth area to be included

within the urban growth boundary. It also should include and explain

the population projections and land demand calculations used to estab-

lish the line.

An urban growth boundary should be clearly shown in the comprehen-

sive plan in order to determine whether a particular property lies within,

or beyond, the boundary. When confusion arises over the location of

property vis-a-vis the boundary, there must be a specific process and

criteria for resolving the issue.

The zoning ordinance must limit development in areas lying beyond the

growth boundary. This may be done by enacting restrictive agricultural

or conservation zoning to prevent major subdivision and commercial

development beyond the boundary, combined with techniques to attract

growth to appropriate areas. These techniques can direct development to

lands within the line where adequate supporting infrastructure is avail-

able. In some instances, this also may require downzoning land immedi-

ately beyond the boundary to restrict urban or suburban scale

development that would be allowed under existing zoning.

Comprehensive rezoning can be a particularly strong tool for the creation

of urban growth boundaries in this state. In Maryland, the reclassifica-

tions resulting from a comprehensive rezoning action have the legal

The Line Should be

Clear

The Zoning Ordinance

Must Support the

Boundary

28

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

presumption of validity as long as proper analyses of land use preceded

the rezonings. Growth boundaries resulting from such actions thus have

the double advantage of being supported by appropriate land use study

as well as the legal validity that results.

With the possible exception of rural settlements or villages that act as

secondary growth nodes, dense or intense zones must be limited to land

within the boundary to promote development there. Care must be taken

even when allowing infill and other limited development within or

around such rural concentrations. Clustering and requirements for

consistency of new construction with existing development should be

strongly encouraged in those areas to avoid sprawl and its attendant

consumption of rural land. Two recent Maryland Office of Planning

Models and Guidelines publications of interest to jurisdictions considering

clustering and regulating rural development are: Clustering for Resource

Protection, and Modeling Future Development on the Design Characteristics of

Maryland’s Traditional Settlements. Other measures to encourage develop-

ment within growth boundaries are:

• Transferrable development rights ordinances that encourage

farmland owners beyond the boundary to sell development rights

to owners of developable land within it.

• Agricultural and environmental protection easements to forestall

the conversion of developable land immediately beyond the

boundary, thus reducing pressures to extend that line

• Incentives, such as reduction of lot-size requirements in certain

instances, for those choosing to develop within the boundary.

• Flexibility within the zoning ordinance such as special zoning

classifications or other measures to encourage and facilitate

redevelopment and infill development of vacant, previously

bypassed parcels.

• Streamlining of review to encourage appropriate developments

within the urban growth boundary.

29

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Other than land itself, the availability of infrastructure is most essential

to growth. Jurisdictions with growth area boundaries must provide

sufficient water/sewerage, roads, schools and other public infrastructure

and services to attract the level of population it wishes to locate within

these boundaries. On the other hand, governments should provide only

minimal infrastructure beyond the line to discourage development there.

A jurisdiction can use various mechanisms to create this differentiation of

infrastructure availability:

• Prohibit water and sewerage extensions beyond the boundary

unless needed to eliminate public health problems for which there

are no alternatives.

• Stage utility extensions within the boundary, giving priority to

areas presently served, before extending services.

• Limit capital improvements programs (schools, libraries, major

roads and other infrastructure) to areas within the growth bound-

ary.

• Create different specifications for sizing of roads, schools, and

other infrastructure within and beyond boundary.

• Design utility lines that result in exhaustion of capacity when

they reach the boundary, thus removing “temptation” to extend

them beyond.

The consistency provisions of the Economic Growth, Resource Protection,

and Planning Act contain specific language to support these actions. It

states clearly that local governments may not approve construction

projects involving the use of State funds unless the project is consistent

with the comprehensive plan. A local project may be approved if there

are extraordinary circumstances that warrant proceeding, and if no

reasonably feasible alternative exists.

Interjurisdictional coordination and cooperation are vital for an urban

growth boundary to be successful in controlling growth. First, all juris-

dictions having land within the boundary should be involved in examin-

ing the issues, reviewing data and determining where the boundary will

be drawn. The jurisdictions also must reach agreement on exactly what

proposed plats, site plans, rezonings and other development-related

Public Services and

Infrastructure Must

Support Development

Within the Boundary

and be Minimal

Elsewhere

Interjurisdictional

Coordination Must be

Adequate

30

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

information they will refer to each other for review and comment. These

materials must then be referred in a timely fashion.

Each involved jurisdiction must make every attempt to accommodate the

others’ concerns over a proposed development. Additionally, each

jurisdiction must be continually aware of those developments that lie in

its own territory, but would affect the public services of another. To this

end, a government should seek out the input of the other affected juris-

dictions when such developments are proposed, and work cooperatively

to resolve disagreements and other problems before they arise.

Counties whose land borders a city that has enacted a maximum expan-

sion limits line have an additional special interjurisdictional coordination

role. They should advise prospective developers of the lands lying

within the expansion limits line that those properties will probably be

annexed and then developed under the city’s zoning and other regula-

tions and ordinances. County staff also should advise developers to

meet with the city as soon as possible to learn of its development require-

ments.

A county which establishes an urban growth boundary line should be

sensitive to the fact that the higher level of development within that line

could significantly affect adjacent jurisdictions or be affected by develop-

ment actions there. For this reason it should also effect notification and

other coordinative measures, as necessary, with those adjacent counties

and municipalities.

The local jurisdiction should periodically examine its urban growth

boundary and determine if it should be adjusted. The most appropriate

time to do this is when it updates its comprehensive plan.

The Line Should be

Periodically Updated

31

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

THE URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARY

AND THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN

The urban growth boundary is created to clearly delineate areas of

growth and areas for resource protection. As a definitive line on the

map, the boundary is a local government’s strongest growth manage-

ment statement. For this reason, the boundary must occupy a central

place in the comprehensive plan.

The urban growth boundary should be prominently addressed in the

land use goals and objectives that outline the plan’s broad direction. A

jurisdiction that enacts an urban growth boundary may include it as an

objective subordinate to a more generalized land use goal.

• Goal:

Encourage development and economic growth in areas desig-

nated for growth in the plan and protect agricultural and other rural

lands.

• Objective:

Enact an urban growth boundary that includes those areas that

are presently developed and those where such development is

scheduled in the future.

Or, the enactment of the urban growth boundary could be a goal in its

own right with supporting objectives.

• Goal:

Enact an urban growth boundary to designate areas where

growth and economic development should occur.

• Objectives:

Include all areas reserved for suburban- and urban-scale residen-

tial densities and commercial/industrial intensities within the

boundary.

Amend ordinances, regulations and procedures as necessary so

that they reflect the priorities and intent of the urban growth

boundary.

Develop and enact programs and strategies that support the

urban growth boundary and the target density established for

residential development within the boundary.

Develop and implement programs and strategies that support the

urban growth boundary and direct development away from rural

resource areas.

32

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

Periodically examine the urban growth boundary along with its

supporting programs and strategies. Determine if ongoing devel-

opment trends dictate a change in the boundary, and amend the

comprehensive plan whenever the boundary line is changed. Deter-

mine if changes in ordinances or other implementing mechanisms

are necessary to advance the goals of the urban growth boundary.

Because the placement of infrastructure is central to the effectiveness of

the urban growth boundary, the boundary also should be addressed in

the community facilities goals and objectives.

• Goal:

Provide public facilities and infrastructure in a manner that

supports the urban growth boundary’s delineation of growth areas.

• Objectives:

Use capital programming, water/sewerage planning and other

means to provide for adequate services and infrastructure within

the boundary in order to serve projected growth.

Use these tools to limit public services in areas beyond the urban

growth boundary that are to remain rural/agricultural in use.

Develop specialized standards for roads, schools and other public

facilities that serve the population in non-growth areas.

The goals and objectives of the sensitive areas element also should reflect

the growth boundary.

• Goal:

Protect sensitive environmental features within the urban growth

boundary.

• Objectives:

On watersheds lying within the urban growth boundary, deter-

mine which portions of each watershed should be excluded

entirely from development and which can be developed given

proper management procedures.

Develop within the boundary in a pattern that will present the

least amount of runoff threat to water quality.

Adopt flexible and innovative regulations that facilitate develop-

ment within the boundary in a manner that achieves density

targets and protects sensitive areas.

33

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The comprehensive plans and zoning ordinances of each Maryland

jurisdiction using urban growth boundaries, were reviewed as part of

this project.

Other sources of information were:

• Frederick City and Frederick County Departments of Planning

and Zoning, Frederick City-Frederick County Joint Comprehensive

Plan Coordination and Annexation Limits Study Committee Report,

Frederick, Maryland, 1988

• Washington County Planning Department, Washington County,

Maryland Comprehensive Plan Status Report, 1991

• V. Gail Easley, AICP, Planning Advisory Service Report 440, Staying

Inside the Lines: Urban Growth Boundaries, 1992

• Governor’s Office of Planning and Research and Governor’s

Interagency Council on Growth Management, Urban Growth

Boundaries, Sacramento, California, 1991

34

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

APPENDIX:

MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN

MONTGOMERY COUNTY AND THE CITIES OF

ROCKVILLE AND GAITHERSBURG

The following is the full text of the Memorandum of Understanding

about Urban Growth Areas that was signed by the Montgomery County

Executive and the Mayors of Rockville and Gaithersburg. This document

was signed on July 23, 1992.

All parties to this Memorandum of Understanding share the conviction

that the area’s quality of life is dependent upon the maintenance of

economic vitality. It is the economic base that helps provide the re-

sources to support the services which make living in this area so attrac-

tive.

In order for Rockville, Gaithersburg, and Montgomery County to con-

tinue the quality of life people have to come to expect, it is essential that

all jurisdictions support well-managed economic development and

housing initiatives which will be mutually advantageous to all parties,

and agree to the goals and principles of the General Plan.

Therefore, the Montgomery County Executive and the County Council of

Montgomery County, sitting as the District Council, the Mayor and

Council of the City of Rockville, and the Mayor and Council of the City

of Gaithersburg agree to the following:

1. The City Councils, the County Council, and the Executive agree to

work cooperatively to determine logical urban growth areas and to

established boundaries which will serve as guidelines for a twenty-

year planning horizon regarding:

1) Land use and required community facilities,

2) Capital investment responsibilities, and

3) Logical and efficient operating service areas.

2. Montgomery County will base its position of support on annexations

upon the above three considerations and the designation of logical

urban growth areas by Rockville and Gaithersburg. The Cities and

the County will develop procedural guidelines for handling annex-

ation agreements.

3. Rockville and Gaithersburg recognize the County’s goal of requiring

adequate public facilities in order to assure managed growth and

acknowledge their accountability for the cooperative achievement of

such goals. Within its boundaries each City will, however, assume

responsibility for and determine how those goals should be measured

35

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

and attained. It is the mutual intent of all parties that project funding

and staging will relate to the timing of public facility availability and

to that end will consult with each other as necessary to assure attain-

ment of desired goals.

4. The County recognizes the ability of the two Cities to develop and

implement public interest solutions to growth management concerns.

City or County development plans for land located within the urban

growth areas and on adjacent areas should seek to achieve the land

use, transportation, and staging objectives of each of the affected

jurisdictions, as defined in duly Approved and Adopted master,

Sector, or Neighborhood Plans. Every effort should be made by all

parties to reconcile any differences in those objectives.

5. The City Councils, the County Council, the Executive, and the Mont-

gomery County Planning Board agree to work on a cooperative basis

in the development of plans and programs, including development

districts, that affect parcels within the urban growth areas. Changes

in land uses, staging, or zoning proposals for parcels within the

urban growth areas will only be undertaken after the participation

and consultation of the other parties. Any land annexed by either

Gaithersburg or Rockville should included a staging component in

the annexation agreement.

6. Rockville and Gaithersburg endorse the R & D Village concept out-

line in the Shady Grove Study Area Adopted Plan as being in the best

interest of both Cities and the County.

7. Rockville and Gaithersburg recognize the importance of creative

development initiatives such as Moderately Priced Dwelling Units

(MPDU) and Transferable Development Right (TDR). The Cities will

continue to utilize these and other appropriate innovative concepts to

further the common development goals for the area.

8. The Cities will cooperate in a master traffic control plan and transpor-

tation (including transit) system for the County.

9. The principles contained within this Memorandum are meant to

apply to all future actions pertaining to land in the Cities or on or

near the Cities’ borders.

10. We recognize the importance of moving ahead on an early basis to

establish a schedule of action and agree to meet frequently on these

important issues.

36

Maryland's Models and Guidelines Vol. 12-Urban Growth Boundaries

OTHER PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE

The Maryland Office of Planning's Series: Managing Maryland's Growth

Models and Guidelines Procedures for Review of Local Construction Projects;